Vision: Biodiversity is valued, resilient and flourishing.

Biodiversity is a modern term to describe all life forms including different plants, animals, micro and macroorganisms, their genetic diversity and the ecosystems where they connect. Biodiversity captures the living elements of natural systems, but there are also many non-living habitat elements, such as topography, weather, climate, fire, flood, fallen logs, rocks and leaf litter. Native vegetation, soil biology, nutrient and carbon cycles and fungi keep the natural system functioning so the diversity of life can evolve.

Traditional Owners have intrinsically managed the land for the survival of all living things for tens of thousands of years. More recently, land managers, community groups and organisations have also played an important stewardship role in protecting and enhancing biodiversity.

Community aspirations identified throughout this strategy rely on natural systems thriving. However, much of what we do impacts the natural systems, including historic and current land clearing, land use, pest plants and animals and a lack of understanding of Traditional Owners’ traditional ecological knowledge. These impacts will be compounded as climate change increasingly affects weather patterns.

The transformation of the Victorian landscape through changes in land use has pushed many native species and ecological communities beyond critical tipping points such that their resilience is reduced and populations continue to decline. At the same time, the community (residents and visitors) increasingly value and use nature for amenity and recreation.

While individuals, community groups and organisations across the catchment have made significant contributions to the protection and enhancement of the catchment’s biodiversity, the condition for biodiversity has been rated poor since 2009. The long-term risk of further decline remains very high. At the scale that revegetation and natural regeneration occurs across the catchment, the current rate of change is not sufficient to ensure functioning systems where all species can thrive. Large-scale, urgent action is required on public and private land to reverse the historic impacts and improve biodiversity resilience.

While recognising the complexity of natural systems, and because biodiversity contains so many elements, we need to narrow our focus to a few key principles that are fundamental to the entire ecosystem. The biodiversity theme of this strategy focuses on terrestrial native vegetation. Riparian, aquatic and wetland biodiversity are covered in the water theme, and soil biodiversity is covered in the land theme. Furthermore, actions to increase community engagement in NRM, including biodiversity, are included in the community theme. All these themes are connected through natural systems and management.

Native vegetation, along with other elements, provides key habitat for much of the wildlife above and below the ground. Improving native vegetation and its connection to the other habitat elements is critical to saving endangered and threatened species. Native vegetation is critical to the resilience of the catchment’s biodiversity.

The 4 key principles to understand and manage native vegetation for biodiversity health are:

- increase native vegetation extent

- increase habitat quality in native ecological communities on public and private land

- improve landscape context or pattern of native vegetation

- prioritise habitat management for threatened species, ecological communities and increased system function.

These principles form the basis of the biodiversity theme.

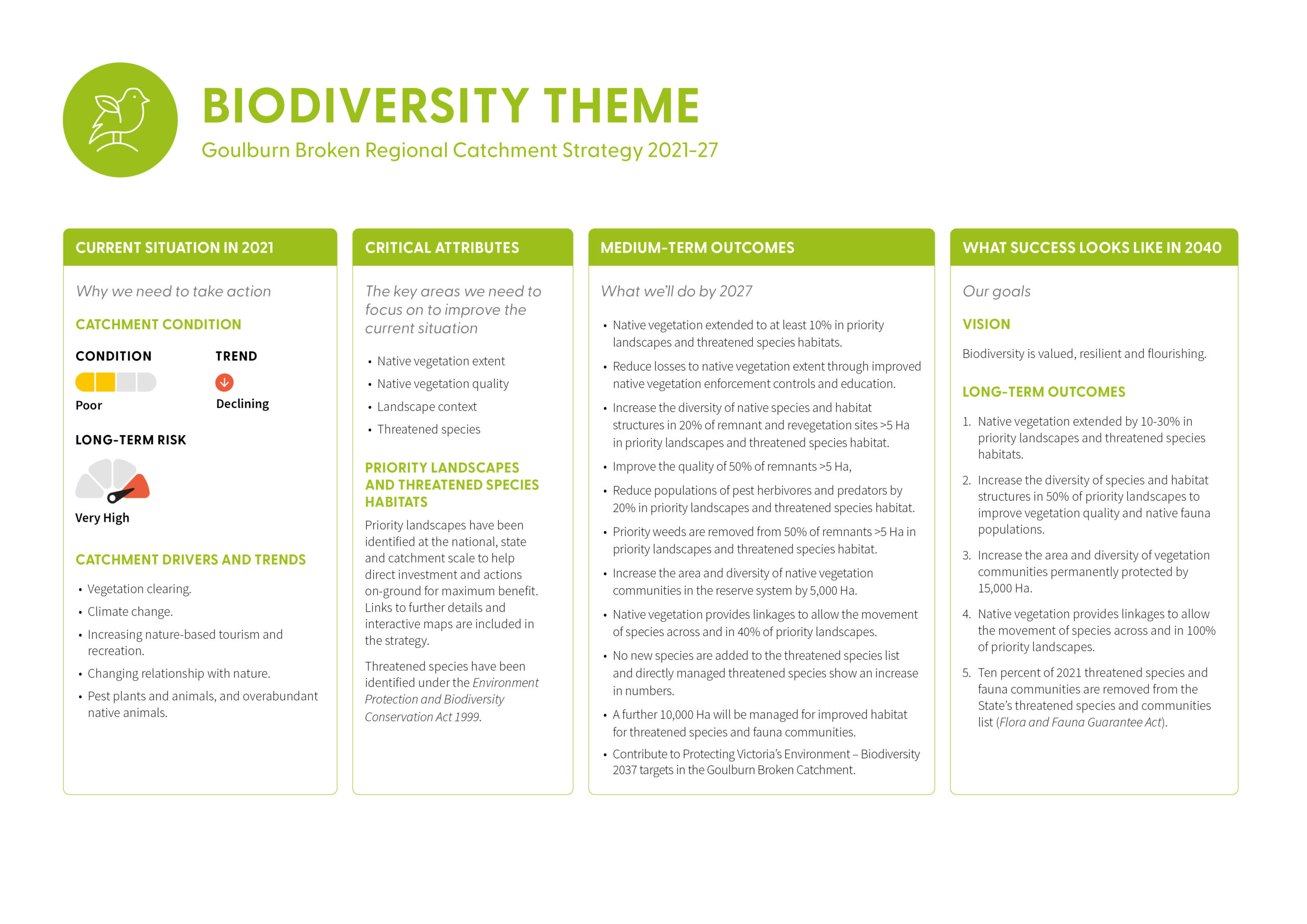

A snapshot of the biodiversity theme of the strategy is provided in Figure 31, click on the tabs below for further detail.

Background

Types and location of native vegetation

Many different native ecological communities are found across the catchment, depending on factors such as topography, soil types and rainfall (Revegetation Guide for the Goulburn Broken Catchment). Vegetation can be found as remnants on private land, public land such as national parks, reserves and roadsides, and along waterways. It is important that these remnants are managed as many are declining in quality due to threats such as pest plants and animals, bushfires, small size and lack of connection to other remnants.

Some common vegetation types include:

- red gum forest in the Barmah and Lower Goulburn national parks, along waterways and in the Riverine Plains

- plains grassy and box-gum woodlands and associated pine-buloke woodlands in the Riverine Plains, Broken Boosey State Park, and remnants on private land (large, old paddock trees)

- box-Ironbark Forest in the Heathcote-Graytown National Park and Reef Hills State Park.

- plains grasslands scattered across the plains

- seasonal herbaceous wetlands across the plains

- wet forest and alpine bogs in the mountains interspersed with small areas of temperate rainforest.

Most of the catchment’s native ecological communities are found on public land which covers one-third of the catchment and includes hills, mountains and less-fertile country. Public land is often viewed as the keeper of biodiversity due to the extent of native vegetation, diversity of species and quality. However, many significant remnant native ecological communities are found on private land. Private land covers two-thirds of the catchment, of which approximately 10-20% is covered by native vegetation in small and large patches and are of varying quality. Importantly, 70% of native species rely on private land for all or some of their life cycle. Private land management has a significant stewardship role in the protection and enhancement of native vegetation.

Native vegetation decline

Clearing for agriculture and urban development was widespread and relatively fast paced from the 1880s to the 1950s, removing large areas of native vegetation and transforming the landscape. This resulted in reduced habitat, changes to ecosystem processes and the extinction of several species of flora and fauna with many others under threat of extinction. This is referred to as the ‘extinction debt’ from past clearing with ongoing decline in many species that were once common.

Many land managers are improving their practices and carrying out revegetation that has a positive effect on native vegetation extent and condition. However, overall native vegetation quality is declining and the landscape context/patterns are changing due to past practices, altered fire regimes, pest plant and animal impacts and the compounding effects of climate change. Furthermore, while Victorian native vegetation regulations have slowed the rate of clearing, legal and illegal clearing still occurs with native vegetation reducing by 4,000 habitat hectares each year in Victoria (Biodiversity 2037). All of these factors increase the importance and value of the remaining native vegetation in the catchment.

Across the catchment, there are approximately 2,750 native plant species, of which 13% are threatened, and 493 vertebrates, of which 22% are threatened. Very little is known about the invertebrate fauna, but threatened species include the golden sun moth. Some species that once occupied the catchment are now extinct, such as the eastern bettong. Many threatened species persist only in small patches of remnant habitat, for example the mountain pygmy-possum in the alpine boulder fields. Protecting and restoring areas of habitat at a large scale is critical to preventing further extinctions.

The approach for biodiversity in this strategy is to provide greater diversity, quality and extent of native ecological communities (and other habitat such as paddock trees) to create functioning systems where threatened and common species can thrive.

Threatened species habitat and ecological communities can be prioritised for management activities, such as remnant protection and revegetation, to improve system functioning. In addition, some individual actions may be needed to protect specific threatened species as the lag time may be too long before system function improves. For example, translocation, supplementary feeding and habitat plantings may be required to help protect the mountain pygmy-possum.

This strategy (and related sub-strategies, such as the Biodiversity Strategy for the Goulburn Broken Catchment 2016-2021) focuses on priority landscapes where actions to improve the native vegetation are likely to have greater success in creating healthy functioning systems that support biodiversity. This prioritisation is key to biodiversity response planning and an important component of the statewide biodiversity plan (Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037).

Key principles of native vegetation management

There are 4 key principles in managing native vegetation for biodiversity, including threatened species and ecological communities. These principles interact in complex ways as part of natural systems.

1. Increase native vegetation extent

Native vegetation extent refers to the area occupied by native vegetation (as opposed to other land uses such as, cropping, grazing of non-native pastures, and urban areas). That is, imagine looking at an aerial photo and looking down on the areas of native vegetation across the landscape. Overall there is not enough native vegetation in the catchment to support the majority of species in the landscape. Increasing native vegetation extent can be achieved through allowing natural regeneration, and active revegetation. It will require a continued effort from land managers, community groups and funding bodies.

2. Increase vegetation quality in native ecological communities on public and private land

Vegetation quality is defined as species diversity and vegetation structure. Species diversity refers to the range of species expected in a particular ecological community, such as heathy dry forests. Vegetation structure refers to the composition of the vegetation in the ecological community.

Increasing vegetation structural diversity provides more diverse habitat areas and therefore more niches where different species can survive. Structural diversity includes:

- a range of ground cover, mid-storey (up to 2 m) and tall upper-storey vegetation depending on the type of vegetation, that is, grasslands would have different structural diversity to tall forests

- a diversity of age structures in vegetation communities as different fauna species use different age structures, for example, recently burnt areas provide habitat for colonising species

- the presence of fallen timber and organic matter, open patterns, changes in topography and other features such as rocky outcrops.

The protection and enhancement of existing native vegetation is critical to increasing vegetation quality across the catchment, particularly for larger remnants and public land. It includes practices such as such as fencing to control grazing, re-establishment of understorey species and pest plant and animal control.

3. Improve landscape context or pattern of native vegetation

Landscape context refers to the patterns in a landscape, which are the size and shape of remnants, distance and connection to waterways and wetlands, distance between remnants, adjacent land use and connectivity. It influences the movement of native species and their resilience to disturbances, although barriers to movement vary for each species. In general, the more linkages between remnants, and less gaps, result in improved species movement (for mating or moving due to climate change) and a more resilient landscape. Increasing connectivity can occur through habitat enhancement such as revegetation corridors, planting new paddock trees and placement of logs.

4. Prioritise habitat management for threatened species, ecological communities and increased system function

While the focus of this strategy is on managing ecosystems and ecological processes for the benefit of all species, specific threat management may be required to meet the unique needs of individual species and ecological communities. In general, activities that focus on individual species and/or populations are resource intensive and there are few success stories (for example, moving individuals from one site to another and captive breeding). Therefore, options need to consider integrating management across landscapes and using collaborative partnerships to improve success. Planning should recognise that threatened species and ecological communities are part of ecological systems.

Biodiversity values and ecosystem services

Surveys show the catchment’s terrestrial biodiversity is valued by the community for its intrinsic and cultural values, and for the ecosystem services supporting agricultural production, tourism, lifestyle and recreation. The concept of intrinsic value is that biodiversity has value in its own right that may or may not benefit humans. An example is the right of Regent Honeyeaters to exist without any benefit to us.

Ecosystem services are the direct and indirect contributions to human wellbeing and ecosystem function. They support survival and quality of life. Ecosystem services include pest management, food, fresh water, shade, pollination, nutrient recycling, medicines, amenity and wellbeing. The key uses of ecosystem services identified by the community are agriculture, lifestyle, forestry, tourism and recreation. They are outlined in Table 73. Many ecosystem services are poorly understood or sometimes not even known until they are lost, such as the importance of gravel beds for fish or perennial vegetation for water tables.

Table 73: Biodiversity values held by the key users of the ecosystem services

| Key users | Biodiversity values |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | Values are around benefits such as soil microbes that keep soil healthy, native vegetation that provides shade and shelter for livestock and habitat for insects and birds and bats that help manage pests and pollinate crops. |

| Lifestyle | Values are around services such as aesthetically pleasing landscapes, clean air, fresh water and wildlife. In addition, there is growing scientific and anecdotal evidence about the mental health and wellbeing benefits. |

| Forestry | Values are around the timber industry and forests that provide timber, firewood, honey production and natural pollination services. Additional values are around recreation, regional tourism, social and community connections, amenity, education, knowledge, health and wellbeing. |

| Tourism and recreation | Value is around healthy natural systems, especially on public land. Examples include intact native vegetation and bush for bushwalking or bird watching, clean water, wildlife, vistas and fresh air. |

Current condition

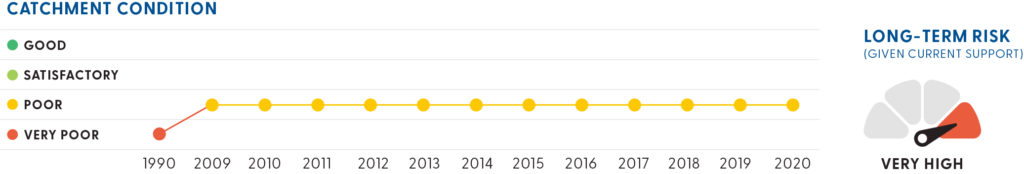

Qualitative condition ratings for the catchment’s biodiversity have been reported by the Goulburn Broken CMA since 1990. These ratings have been drawn from Goulburn Broken CMA annual reports, tipping points described by the community, socio-economic research and the biodiversity theme discussion paper developed as part of the strategy renewal. Figure 32 describes the trends in the condition and the long-term risk of a decline given current support. More information is available in Goulburn Broken CMA annual reports.

Figure 32: Trends in the condition of the Goulburn Broken Catchment’s biodiversity and resilience since 1990 and the long-term risk of decline in condition given current support

Catchment condition for biodiversity is currently rated as poor, with no significant change since 2009. The long-term risk of decline is very high. This is partly due to historic and current land use decisions resulting in:

- a net reduction in native vegetation extent, for example, clearing and logging (while native vegetation off-set policies have failed to stop overall vegetation loss, it would have been greater otherwise)

- a reduction in diversity and quality of native vegetation, for example, firewood collection, frequent burning and increased grazing by pest animals, such as deer, and over-abundant native animals, such as kangaroos

- an intensification of land use and loss of landscape context, for example, the reduced extent and removal of mature trees along corridors and key habitat linkages.

However, this is not to downplay the actions of landholders, community groups and organisations to revegetate, protect and link areas of native vegetation. Every area of habitat increase has a positive effect on the catchment’s biodiversity. There are also increasing opportunities for biodiversity on private land, as farmers meet increasing demand from consumers for greener, more environmentally-friendly products.

The condition of the functional elements (key principles) of native vegetation is listed below.

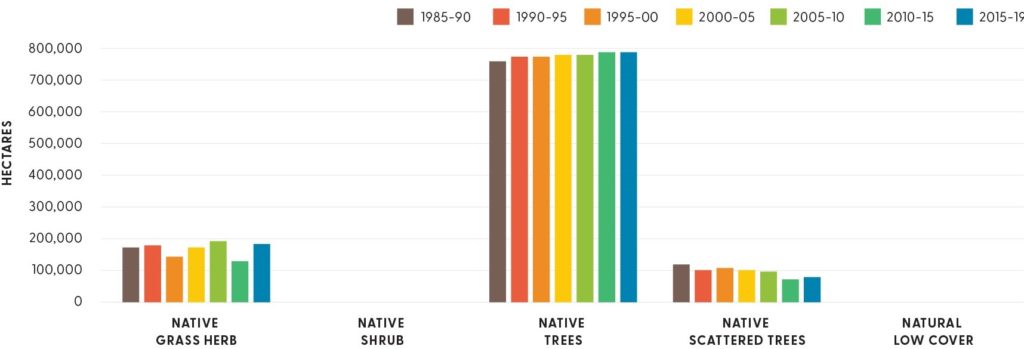

1. Native vegetation extent is poor on private land due to large scale clearing. Historic clearing was at a broadscale. Ongoing clearing or removal of large, old trees has a significant impact, as does incremental losses due to permitted and illegal clearing. Figures 33 and 34 show native vegetation extent and spatial distribution in the catchment.

Source: Victorian Land Cover Time Series (DELWP)

Source: Victorian Land Cover Time Series (DELWP)

2. Quality of native vegetation is poor or declining across the majority of private land, but large areas of improved land management (for example, planting native species) provides potential for future improvement. On public land, quality of native vegetation can be high in large National Parks, but is generally declining in all areas due to threats such as more frequent bushfires, changed fire regimes and increasing pressures from pest plants and animals.

Historic and ongoing threats are also resulting in structural and species diversity decline. connected. For example, historic clearing and overgrazing resulting in simplified landscapes on private land, and continues to affect public land where there are grazing licences.

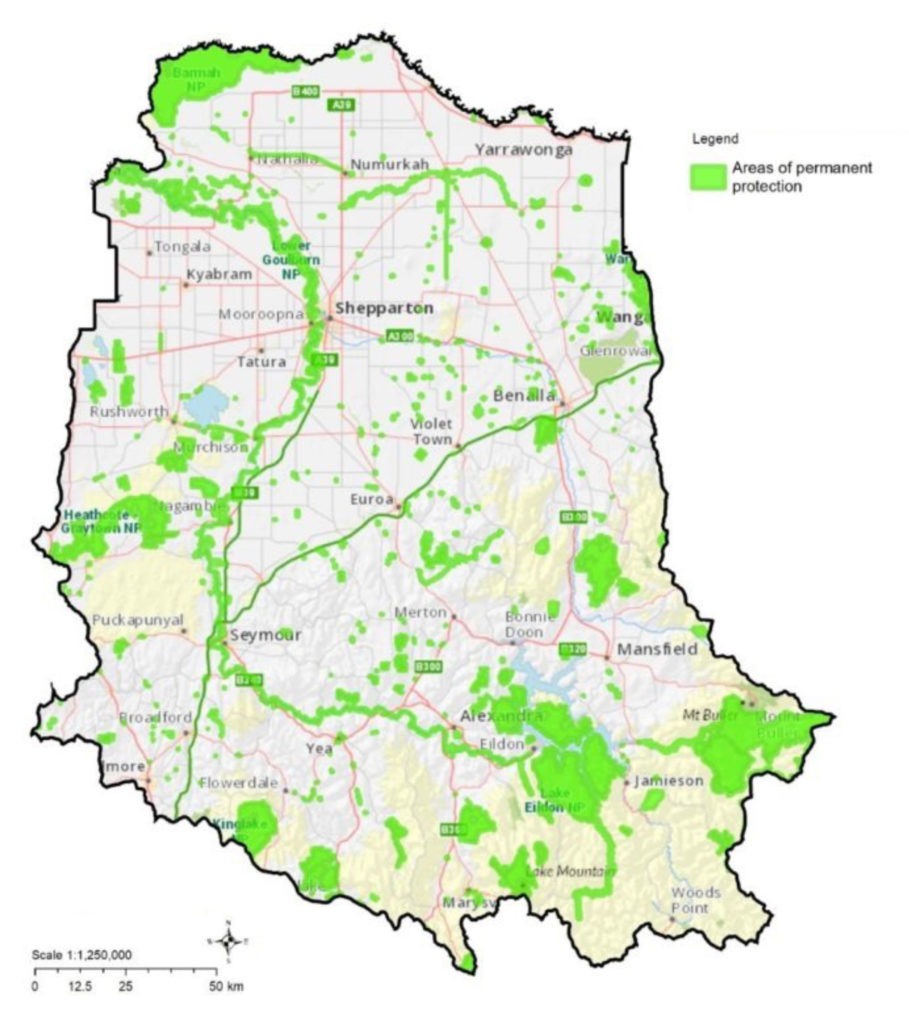

The area of native vegetation under permanent protection may indicate areas of higher native vegetation quality. However, many remnants receive little or no management.

Figure 35 shows the spatial distribution of permanent protection areas in the catchment. Permanent protection areas are defined under the International Union for the Conservation of Nature as an area of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal or other effective means. They include national parks, conservation covenants, and conservation areas.

Source: Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database Terrestrial (CAPAD)

3. Landscape context can be considered in poor condition across much of the fragmented landscapes where private land dominates. Vegetation extent is low, affecting connectivity and linkages across landscapes. There are few large remnants, often with large distances between small remnants that are surrounded by more intensive land use (for example, irrigation). These linkages are further lost with the removal of mature trees or clearing for development resulting in reduce species and movement across the landscape.

On public land, landscape context can be considered high for the large parks and reserves where many ecosystems and ecotones can be found along topographical gradients. However, most of these large reserves are in the hills and high country of the catchment. In these reserves, there are also large areas of public land which can be interspersed with logging coupes and pine forests, which act as barriers to movement for many species. Reserves in agricultural-dominated landscapes are often small (10-40 ha), have poor landscape context, are like islands in a sea of agriculture without corridors, but often have paddock trees which can act as stepping stones for more mobile species such as birds and bats. The harsh edges to the small reserves reduce their actual habitat area through edge effects such as drying winds and weed spread from adjacent land.

4. Threatened species and ecological communities are in very poor condition but not much is known about their current status as no systematic surveys have occurred for many years. We have no understanding of the trajectory of nearly all species or ecological communities. Locations of threatened plant locations are known for some species, but are often happened upon rather than through a systematic search for species. Exceptions include charismatic species such as regent honeyeaters, platypus and swift parrots. Anecdotally, however, previously common species continue to be in decline and more species have been added to the threatened species list.

Drivers of change

Drivers of change influence how the catchment operates and can shape future trajectories of species and ecological communities, landscape context, vegetation quality and extent. What we do now will impact the type of future landscapes we will operate in. Without increasing the native vegetation extent, quality and connectivity, unanticipated or acute shocks, such as heatwaves, bushfires and drought, will compound the already stressed natural systems. We need to build resilience into these systems to reverse declines and threats.

Tables 74-78 outline the 5 major drivers of change impacting biodiversity. They were identified through community engagement and socio-economic analysis as part of the strategy renewal:

- vegetation clearing

- climate change

- increasing nature-based tourism and recreation

- changing relationship with nature

- pest plants and animals.

Driver 1: Vegetation clearing

Table 74: Catchment trends and impacts on biodiversity from vegetation clearing

| Catchment trends | Impacts on biodiversity |

|---|---|

| • Traditional Owner connections to Country are lost. • Habitat extent, connection and quality is lost. • Habitat elements other than trees are lost. • Removal of rare and threatened Ecological Vegetation Classes (EVCs) and transitions or ecotones between EVCs. • Removal of mature trees. • Reduced ecosystem services, such as water quality, pollination, shade and shelter for livestock. • Threatened species continue to decline. • Removal of under-storey, logs and leaf litter to tidy-up land. • Removal of grasslands and derived native grasslands through change in land use, such as from grazing to cropping, grazing to urban development and lifestyle properties. • Changes to soil structure and function. | • Direct loss to extent and connection reduces the ability of species to move through landscapes. This limits access to food and habitat and can create genetic bottlenecks and loss of sub-populations. • Removal of trees results in the removal of associated habitat elements, such as hollows, logs, leaf litter and soil biota that many species rely on, for example mycorrhizal fungi, white-winged choughs, bandy-bandy’s and invertebrates. This reduces the provision of ecosystem services such as shade, shelter and pollination. • As an EVC becomes rarer or extinct, the unique combinations of plants and associated fauna cannot be replaced. • Threatened species and ecological communities are less resilient as habitat is lost, further reducing their ability to adapt to change and more species becoming threatened or extinct. |

Driver 2: Climate change

Table 75: Catchment trends and impacts on biodiversity from climate change

| Catchment trends | Impacts on biodiversity |

|---|---|

| • Hotter and drier climate. • Reduced rainfall in spring and autumn and increased intensity of summer rainfall. • Increased frequency and intensity of storms, heatwaves, bushfires and droughts. • Reduced resilience of ecosystems that are susceptible to a changing climate. • Changes in the connections between species and systems. • Changes in environmental cues for species. | • Climate change has a multiplier effect. For example, heat waves kill individual plants and animals that are already stressed. • Biodiversity generally adapts to drought and floods, however, many plant species will likely suffer or die if these extremes are prolonged. • The extent of drought refugia are reduced when there is decreasing water volume and cease to flow events. • Hotter, larger and more frequent bushfires will kill millions or billions of animals. The recolonisation of areas by different species may take many years (1-100 years) depending on species’ requirements. Species that require a long interval between burns could be lost from landscapes. • Certain ecosystems will be particularly affected by a drier climate as they have a lower tolerance for change. For example, alpine habitats are at risk of tree and shrub invasion and extinction in a drier climate. The loss of these ecosystems will have major consequences for biodiversity. • The connection between natural elements ensures that systems have been viable and functioning for millions of years (albeit changing). The loss of certain elements due to climate change will occur, but we do not know where the tipping points are that result in system collapse. For example, flowering and pollinators may no longer synchronise, resulting in no seed set for plants or food for animals. This may set up a system collapse that is difficult to reverse. |

Driver 3: Increasing nature-based tourism and recreation

Table 76: Catchment trends and impacts on biodiversity from increasing nature based tourism and recreation

| Catchment trends | Impacts on biodiversity |

|---|---|

| • Increasing use of public land, rivers and lakes for recreational activities, camping and weekends away. • Increasing number of visitors from local urban areas and outside the catchment. | • Potential for more people to value nature and be concerned about the management and condition of public land. • Potential to involve visitors in land stewardship such as planting and weed control. • Potential negative impacts due to increased use resulting in more rubbish, tracks, and weed spread. • Incremental loss of groundcover, proliferation of tracks, increasing fragmentation and increased soil compaction and erosion. |

Driver 4: Changing relationship with nature

Table 77: Catchment trends and impacts on biodiversity from a changing relationship with nature

| Catchment trends | Impacts on biodiversity |

|---|---|

| • The people using and influencing natural resources are becoming increasingly diverse with many living outside the catchment. • Catchment residents increasingly value the natural environment to enhance their lifestyle, rather than for earning a living. This is also true of a many visitors who value the catchment’s natural resources for recreational activities such as fishing, camping and skiing. • The people managing the natural resources are not always the same as those using or benefiting from them. • Consumers are increasingly interested in where their food comes from and how it is produced, including the environmental impacts. • Investment from a range of existing and emerging markets, as consumers increasingly demand environmentally-friendly products and businesses, such as natural capital investments and carbon markets. | • Opportunities to engage visitors and recreational users in biodiversity projects, although this may require new engagement methods. • Utilitarian values are common among the general population and do not support biodiversity conservation, for example, the continued loss of nature for growth and economic benefit in the short-term. • Increasing opportunities for biodiversity on-farm to meet increasing demand for greener products, such as organic, carbon neutral, grass fed and native bush food production. |

Driver 5: Pest plants and animals

Table 78: Catchment trends and impacts on biodiversity from pest plants and animals

| Catchment trends | Impacts on biodiversity |

|---|---|

| • Ongoing populations and range of pest herbivores, such as deer, goats, pigs and feral horses, competing for resources and changing vegetation in ecological communities by selective and overbrowsing. • Ongoing populations of pest predators, such as wild dogs, cats and foxes, as some areas become more suitable and transition to urban or lifestyle use. This results in increased threats to rare and threatened species. • Ongoing infestations of weed species such as blackberry, gorse and new and emerging weeds, particularly as the climate changes. • Overabundant native plants and animals due to highly modified landscapes, e.g. kangaroos, noisy miners, red gum seedlings and cumbungi. | • Pest herbivores compete for resources with native herbivores and reduce habitat for native animals. • More predators result in the loss of individuals, which for rare and threatened species can impact on viability. • Loss of system function as key species are lost due to competition for food from predators such as raptors and owls. • Reduction in vegetation quality as weed cover increases, reducing native vegetation extent and diversity. • Soil biology is likely to change with increasing weed cover. • Historic and ongoing management actions such as dams and loss of understorey result in reduced habitat quality and increased pest populations. For example, dams provide water for kangaroos, enabling them to breed continuously. • Overabundant native animals, such as kangaroos and wallabies contribute to overgrazing. • Overabundant aggressive and territorial native birds, such as noisy miners, can outcompete other native birds. • Overabundant native plants in river red gum parks, for example, red gum seedlings, cumbungi and giant rush. |

Tipping points

Understanding and identifying tipping points of significant change is important to increasing the resilience of the catchment and its social, economic and environmental services. Significant change occurs when the characteristics of a system change so much that the system is no longer the same. A tipping point, or threshold, is a critical level of one or more variables. When crossed, it triggers abrupt change in the system that may not be reversible (Wayfinder 2021).

Some tipping points are well understood and can be used to track progress and guide management, while our understanding of others is still developing. It is a key outcome of the strategy to build our understanding of tipping points and how to apply them through partnerships and research projects with a range of organisations.

This strategy outlines which tipping points are important to understand and monitor. In some circumstances tipping points have been exceeded and we need to establish targets to stabilise system function. Further information about tipping points is available here.

Table 79 outlines the data-driven tipping points for biodiversity that will be investigated during the life of the strategy.

Table 79: The data-driven tipping points for biodiversity that will be further investigated during the implementation of the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy

| Critical attribute | Tipping points of interest |

|---|---|

| Native vegetation extent | • Identify the percentage of native vegetation extent in priority landscapes and regions required to support the majority of fauna. |

| Native vegetation quality | • Identify the minimum percentage of species (from the benchmark for each EVC) needed in all remnants and revegetation sites likely to provide high quality habitat for the majority of species. • Identify the minimum percentage of each pre-1750 EVC that needs to be protected and managed for the EVC to be resilient to change. |

| Landscape context | • Identify the minimum percentage of revegetation activities required in high or very high priority linkage areas to improve landscape connection. |

| Threatened species | • Identify the habitat quality and extent that influences threatened species recovery. •Identify when threatened ecological communities become novel and no longer resemble the original community. |

Outcomes and strategic directions

Vision

Biodiversity is valued, resilient and flourishing.

Outcomes and strategic directions

Table 80 outlines long (20-year) and medium-term (6-year) outcomes for the catchment’s biodiversity, which contribute to the state-wide biodiversity plan targets (Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037). It also presents priority directions under each long-term outcome. Please note, the outcomes are complementary and consideration of all outcomes is required during implementation to achieve the vision.

Table 80: Desired long (20-year) and medium-term (6-year) outcomes for the catchment’s biodiversity and associated strategic directions

| Long-term outcomes (by 2040) | Medium-term outcomes (by 2027) | Strategic directions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Native vegetation is extended by 10-30% in priority landscapes* and threatened species** habitats. | • Native vegetation is extended to at least 10% in priority landscapes and threatened species habitats. • Reduced losses to native vegetation extent through improved enforcement controls and education. | • Increase the area of priority landscapes and threatened species habitats by protecting remnant vegetation and planting native vegetation. • Focus efforts on priority landscapes and threatened species habitats. • Reduce the loss of priority landscapes and threatened species habitats through increased compliance with clearing regulations, improved permanent protection, and management of more remnants. |

| 2. Increase the diversity of native species and habitat structures in 50% of priority landscapes* to improve vegetation quality and native fauna populations. | • Increase the diversity of native species and habitat structures in 20% of remnant and revegetation sites >5 ha in priority landscapes and threatened species habitat. • Improve the quality of 50% of remnants >5 ha. • Reduce populations of pest herbivores and predators by 20% in priority landscapes and threatened species habitat. • Priority weeds*** are removed from 50% of remnants >5 ha in priority landscapes and threatened species habitat. • Protecting Victoria’s Environment- Biodiversity 2037 contributing targets: – 264,000 hectares in priority locations are under sustained herbivore control in the Goulburn Broken Catchment. – 40,000 hectares in priority locations are under sustained predator control in the Goulburn Broken Catchment. – 56,000 hectares in priority locations are under sustained weed control in the Goulburn Broken Catchment. | • Increase the diversity of species and structures in remnant and revegetation sites in priority landscapes including threatened ecological communities and threatened species habitats. • Understand and describe the structural diversity required for priority landscapes including threatened ecological communities and to provide habitat for threatened species. • Reduce populations of pest animals and weeds, and overabundant native species in priority landscapes and threatened species habitats. |

| 3. Increase the area and diversity of native ecological communities permanently protected by 15,000 ha. | • Increase the area and diversity of native ecological communities in the reserve system by 5,000 ha. • Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037 contributing target: – Additional 4,500 ha (since 2017) of new permanently protected area on private land is established in the Goulburn Broken Catchment. | • Mechanisms for permanent protection are expanded and increasingly valued. |

| 4. Native vegetation provides linkages to allow the movement of species across and in 100% of priority landscapes. | • Native vegetation provides linkages to allow the movement of species across and in 40% of priority landscapes. • Protecting Victoria’s Environment- Biodiversity 2037 contributing target: – Additional 15,500 ha (since 2017) of revegetation in priority locations for habitat connectivity is established in the Goulburn Broken Catchment. | • Identify and build awareness of the native vegetation linkages that are a priority under a range of climate scenarios. • Increase the revegetation and protection of priority linkages between wetlands, waterways and remnants. |

| 5. Ten percent of 2021 threatened species and ecological communities are removed from the State’s threatened species and ecological communities list (Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act). | • No new species are added to the threatened species list and directly managed threatened species show an increase in numbers. • A further 10,000 ha is managed for improved habitat for threatened species and ecological communities. | • Increase the understanding of tipping points for threatened species and ecological communities to inform management actions considering climate change and extreme events. • Management actions implemented for threatened species and ecological communities are designed to achieve co-benefits. • Systematic surveys of species using the latest technology increase our understanding of the trajectory of threatened species. |

**Threatened species as identified under the National Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, click here for further details.

***Priority weeds as identified in the Goulburn Broken Biosecurity, Invasive Plants and Animals Strategy 2019-2025, click here for further details.

Priority landscapes

Priority landscapes and threatened species habitats have been identified by the Goulburn Broken CMA to help direct investment and actions on-ground for maximum benefit and cost-effectiveness. State and federal governments have also identified priorities. Priorities at the catchment, state and national scale include:

- Catchment scale: The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), in collaboration with key land management agencies and partners (for example, TLaWC, YYNAC, Parks Victoria and Goulburn Broken CMA) have identified priority landscapes at the catchment scale. This was based on local knowledge and previously identified priority areas. An interactive map can be viewed here. For further information refer to the Biodiversity Strategy for the Goulburn Broken Catchment 2016-2021.

- State scale: DELWP have spatial tools (NaturePrint and Strategic Management Prospects) to help make choices about what actions to take, and where, to protect Victoria’s environment and plan for the future. They provide effective management decisions to deliver the statewide biodiversity plan – Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037. NaturePrint can be viewed here and Strategic Management Prospects here.

- National scale: The Australia Government has identified priority threatened ecological communities at a national level. View the map here. Included in the priorities are the Grey Box Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of south-eastern Australia which are found across significant areas of the catchment. This also aligns with the National Threatened Species Strategy, which can be viewed here, and the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act Threatened List, which can viewed here.

Alignment with Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037

Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037

This strategy aligns with and contributes to the state-wide biodiversity strategy Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037. Biodiversity 2037 aims to stop the decline of Victoria’s biodiversity and achieve overall biodiversity improvement by 2037 through the achievement of two overarching goals:

- Victorians value nature

- Victoria’s natural environment is healthy.

This is in line with this strategy’s vision for biodiversity: Biodiversity is valued, resilient and flourishing.

Community members and organisations in the Goulburn Broken Catchment have contributed information and ideas to Biodiversity 2037. This includes identification of the catchment scale priority lanscapes outlined earlier.

Table 81 outlines how this this strategy contributes to Biodiversity 2037.

Table 81: Strategic alignment between the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy 2021-2027 and Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037.

| Biodiversity 2037 priorities | Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy theme area | Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy priority action examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chapter 3: A fresh vision for Victoria’s biodiversity in a time of climate change (1) Deliver cost-effective results utilising decision support tools in biodiversity planning processes to help achieve and measure against the targets. (2) Increase the collection of targeted data for evidence-based decision making and make all data more accessible. | See biodiversity theme, Tables 80-84. | • Deliver cost-effective results utilising decision support tools in biodiversity planning processes to help achieve and measure against the targets. • Quantify the value of increasing native vegetation extent, such as carbon, health, economic and ecosystem services and integrate in decision-making tools. • Conduct scientific research to improve our understanding of the impacts of pest plants and animals on biodiversity, priority landscapes and the impacts of different control options. |

| Chapter 4: A healthy environment for healthy Victorians (3) Raise the awareness of all Victorians about the importance of the state’s natural environment. (4) Increase opportunities for all Victorians to have daily connections with nature. (5) Increase opportunities for all Victorians to act to protect biodiversity | See biodiversity theme, Table 80. See community theme, Tables 97-99. See water theme, Table 124. | Biodiversity theme: • Urban communities are contributing time and financial resources to remnant protection and revegetation projects. Community theme: • Understand and build on the diversity of connections and benefits the community has with the environment. • Identify the NRM related boards and advisory groups in the catchment and provide pathways to diversify their membership. • Create volunteer opportunities for visitors. Water theme: • Quantify and build awareness of the increased economic, lifestyle and health benefits from healthy waterways and native vegetation. |

| Chapter 5: Linking our society and economy to the environment (6) Embed consideration of natural capital into decision making across the whole of government, and support industries to do the same. (7) Help to create more liveable and climate-adapted communities. (8) Better care for and showcase Victoria’s environmental assets as world-class natural and cultural tourism attractions | See biodiversity theme, Tables 80-84. See community theme, Table 97 and 99. See land theme, Table 108 and 109. | Biodiversity theme: • Increasing numbers of landholders are engaged in carbon offset schemes. • Research, particularly around the effects of climate change, is strengthening knowledge to protect, grow and enhance key linkages.` Community theme: • Support nature-based tourism to increase community connection with nature and provide economic benefits to the catchment. • Quantify the public benefits provided by NRM, such as health and recreation. • Investigate and develop programs that successfully engage visitors and corporate volunteers in NRM. Land theme: • Climate change mitigation is an integral part of all land management. |

| Chapter 6: Investing together to protect our environment (9) Establish sustained funding for biodiversity. (10) Leverage non-government investment in biodiversity. (11) Increase incentives and explore market opportunities for private landholders to conserve biodiversity | See biodiversity theme, Tables 80-82. See land theme, Table 108 and 109. See water theme, Tables 124 and 125. | Biodiversity theme: • Develop and test alternative methods of funding revegetation on private land, such as loans, stewardship payments, natural capital investments and land trusts. • Landholders are funded through a range of mechanisms including carbon offsets, incentives, corporate partnerships, natural capital investments and loans for revegetation and remnant protection to increase natural values (habitat for local fauna and flora) and for the ecosystem services they provide (carbon sequestration, aesthetics, productivity, recreational opportunities and health). Land theme: • Support the development of mechanisms that credit private and public landholders and managers for the ecosystem services they provide the community, such as carbon sequestration, habitat provision and biodiversity conservation. Water theme: • Visitors and communities pay for and actively seek opportunities to reduce their impacts on riparian and aquatic biodiversity, for example, camping fees for rubbish removal. |

| Chapter 7: Biodiversity response planning (12) Adopt a collaborative biodiversity response planning approach to drive accountability and measurable improvement. (13) Support and enable community groups, Traditional Owners, non-government organisations and sections of government to participate in biodiversity response planning. | See biodiversity them, Table 81. See community theme, Table 98. | Biodiversity theme: • Regional and local strategic plans (for example, Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy, local government environmental strategies) guide public and philanthropic investment in native vegetation management and improvements. Community theme: • Public land managers and government organisations regularly consult and collaborate with Traditional Owners on NRM planning and implementation. • All stakeholder groups in the community have a voice in NRM decision making at local and regional scale, for example, different livelihood, lifestyle, ethnic, cultural and age groups. • Create decision-making processes at the local and regional scale that reflect the community diversity. |

| Chapter 8: Working with Traditional Owners and Aboriginal Victorians (14) Engage with Traditional Owners and Aboriginal Victorians to include Aboriginal values and traditional ecological knowledge in biodiversity planning and management. (15) Support Aboriginal access to biodiversity for economic development. (16) Build capacity to increase Aboriginal participation in biodiversity management. | See biodiversity theme, Tables 80-81. | Biodiversity theme: • Strengthen support and funding for Traditional Owners to revegetate and manage land for cultural and business reasons. • Traditional Owners are revegetating large tracts of land for cultural and business reasons. • Cultural burning objectives are built into fuel management practices to better engage Traditional Owners in land management |

| Chapter 9: Better protection and management of our biodiversity (17) Deliver excellence in management of all land and waters. (18) Maintain and enhance a world-class system of protected areas. | See biodiversity theme, Tables 80-84. | Biodiversity theme: • Tipping points for threatened species and ecological communities are well-understood and actions are in place to ensure long-term viability of species. • Governments are increasing investment in the National Reserve System through a range of mechanisms. |

| Chapter 10: Government leadership in delivering the Plan (19) Adopt a whole-of-government approach to implementing the Plan. (20) Establish a transparent evaluation process to report on progress towards delivering the Plan. | See community theme, Table 98. | Community theme: • Create links between government and community to enable issues to be heard where and when decisions are made. |

Priority actions

Priority actions give ideas and options for the future, rather than fixed work plans. The actions must evolve as the catchment changes and new information becomes available.

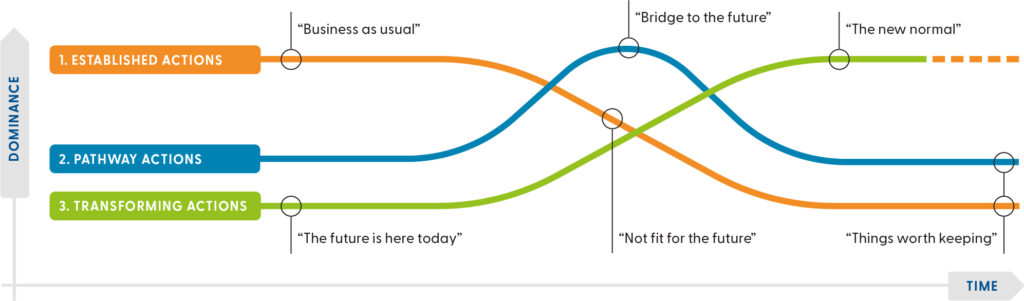

Tables 82-86 present priority actions for each long-term outcome as:

- Established actions, which are those currently occurring that we would like to continue. These include business as usual, recognised and existing practices. These actions are widespread and well-understood.

- Pathway actions, which are innovations that help us shift from the current situation to an ideal future. For example, experiments, bridging or transition actions that take place during the transition from established to transforming actions.

- Transforming actions, which are the way we want things to work in the future. For example, the new normal, visionary ideas and new ways of doing things to create change. There may be pockets of these already happening.

A combination of all 3 types of actions is required to achieve the vision for the future (Figure 36).

Dividing actions this way is based on the Three Horizons framework and helps communities:

- think and plan for the longer-term by identifying emerging trends that might shape the future

- understand why current practices might not lead to a desired future

- recognise visionary actions that might be needed to get closer to a desired future.

Implementation plan

In addition to the overarching vision, outcomes and priority actions, an implementation plan will be developed. It will involve collaboration and knowledge sharing between government agencies, non-government organisations, Traditional Owners, community groups, networks and individuals. The implementation plan will outline roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders and key initiatives delivered in priority landscapes.

Long-term outcome 1: Native vegetation is extended by 10-30% in priority landscapes* and threatened species** habitats by 2040

Table 82: Priority actions required to help achieve long-term outcome 1

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established | • Strengthen support and funding for Traditional Owners to revegetate and manage land for cultural and business reasons, in line with their Country Plans. • Increase the amount of funding available for land managers for remnant protection, revegetation and natural regeneration in priority landscapes and regions. • Seedbanks deliver long-term seed supply to the revegetation industry. • Increasing numbers of land managers are voluntarily revegetating their properties for multiple benefits. • Strive to ensure that clearing of native vegetation follows the avoid, minimise and offset permit process. • Monitor changes in native vegetation extent using agreed assumptions. • Raise awareness among land managers of the benefits of biodiversity for recreation, agriculture and carbon offsets. • Roadside vegetation, paddock trees, public forests, parks and reserves are increasingly valued by community, and are promoted, managed and funded in a variety of ways. For example, Traditional Owner work contracts, Good Neighbour and stewardship programs. • Create opportunities for urban communities to understand and contribute to remnant protection and revegetation projects. • Promote opportunities for community members to connect with nature and enhance biodiversity e.g. Victoria it’s our nature website. • Renew the regional biodiversity implementation plan to coordinate action and investment across a range of partners to increase native vegetation extent. • Implementation of the Victorian Forestry Plan to phase out all native timber harvesting by 2030, while supporting workers, businesses and communities. • Protect remnant vegetation by creating immediate protection areas (such as the Strathbogie Ranges), giving additional protections for old growth forests and improving management of Victoria’s forest (for example, review of the code of forest practice for timber harvesting, major event review of regional forest agreements). |

| Pathway | • Promote the urgency of action to conserve biodiversity through a systems approach, as a priority for political, economic and social agendas. • Develop and test alternative methods of funding remnant protection and revegetation on private land, such as loans, stewardship payments, natural capital and land trusts. • Seedbanks and seed orchards are fully funded, valued and supported as ethical and quality seed reserve for native vegetation programs in the catchment. • Corporate and family farms are implementing large-scale remnant protection and revegetation projects to sequester carbon, provide carbon offsets and meet community expectations. • Strengthen the power and enforcement of native vegetation clearance regulations through statewide planning scheme amendments, clarifying roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of regulators. The amendments should also consider the significance of the biodiversity loss at a local scale (for example, biodiversity loss in very intact ecosystems should be valued differently to low pathway and fragmented areas). • Increasing number of landholders are engaged in carbon offset schemes. • Climate change is an important consideration in all revegetation decisions. • Quantify the value of increasing native vegetation extent, such as carbon, health, economic and ecosystem services and integrate in decision-making tools. • Urban communities are contributing time and financial resources to remnant protection and revegetation projects. |

| Transforming | • All land managers undertake stewardship actions to protect or enhance native vegetation. • Traditional Owners are revegetating and managing large tracts of public land for cultural and business reasons, in line with their Country Plans. • Traditional ecological knowledge influences management practices on private land. • Traditional Owners are healing cultural landscapes through application of cultural and NRM practices. • A fully self-sustaining seedbank centre supplies the catchment’s indigenous seed requirements. • Landholders are funded through a range of mechanisms including carbon offsets, incentives, corporate partnerships, natural capital investments and loans for revegetation and remnant protection to increase natural values (habitat for local fauna and flora) and for the ecosystem services they provide (carbon sequestration, aesthetics, productivity, recreational opportunities and health). • Council planners proactively work with developers to improve vegetation clearance control regulation and enforcement, with an interpretation that reflects the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy’s biodiversity outcomes. • Stronger vegetation clearing controls are enforced effectively to reduce illegal clearing and ensure planning overlays are robust in conserving remaining native vegetation and allowing for future linkages (such as, ensuring development allows for corridors). • Biodiversity research and management decisions consider climate change, resulting in adaptation and mitigation. • Revegetation species are genetically diverse, improving their capacity to adapt to climate change and other shocks and disturbances. • Roadside vegetation, paddock trees and Nature Conservation Reserves are fully protected and provide connection across the landscape. • Water requirements of private properties are managed sustainably, and if dams are retained they are fenced-off from livestock and acting as wetlands providing multiple benefits for livestock and biodiversity. |

Long-term outcome 2: Increase the diversity of native species and habitat structures in 50% of priority landscapes to improve vegetation quality and native fauna populations by 2040

Table 83: Priority actions required to help achieve long-term outcome 2

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established | Increasing species diversity and habitat structures • Increase the percentage of revegetation carried out that reflects EVC benchmarks as much as possible, given availability of species as seed or tubestock. • Identify research projects to address issues in meeting EVC benchmarks, and measuring and improving soil moisture retention and carbon storage functions of native vegetation areas. • Strengthen the impact of seed banks, seed production areas and genetic knowledge on the viability of seeds for a small number of plant species. • Increase the area of voluntary covenants secured on private land. • Advocate for the regulation of a native vegetation clearing offset. • Regional and local strategic plans guide public and philanthropic investment in native vegetation management and improvements. • Increase the number of compliance officers and resources to enforce native vegetation rules and regulations, such as illegal firewood collection, clearing and rubbish dumping. • Deliver cost-effective results using decision support tools in planning to help achieve and measure against targets. • Renew the regional biodiversity implementation plan to coordinate action and investment across a range of partners to increase species diversity and habitat structures. Pest plants and animals • Increasing coordination and management of pest plants and animals on public and private land. • Conduct scientific research to improve understanding of the impacts of pest plants and animals on biodiversity, priority landscapes and different control options. • Pest plant and animal management is conducted with complimentary practices such as revegetation to reach objectives of increased vegetation quality. • The Goulburn Broken Biosecurity, Invasive Plants and Animal Strategy is implemented and adapted to achieve catchment-scale pest plant and animal management. • Deliver cost-effective results using decision support tools in planning to help achieve and measure against the targets. |

| Pathway | Increasing species diversity and habitat structures • Integrate structural elements (such as logs, snags, rocks and food plants), artificial structures (such as nest-boxes and paddock tree guards), rewilding and inoculation of soils and leaf litter in relevant habitat restoration activities. • Increase the area of ground cover at remnant and revegetation sites. • Modify fuel reduction burns to retain vegetation quality, maintaining soil moisture and carbon storage. • Research projects into propagation and direct seeding, rewilding and other habitat enhancement techniques result in increasingly diverse ecosystems. • Increase availability of diverse species in revegetation programs through maintained seed production areas. • Increase capacity of seed banks and nurseries to supply native seed and tubestock. • Increase cultural management of Country by Traditional Owners. • Cultural burning objectives are built into fuel management practices. • Climate change is considered in management decisions to improve the quality of native vegetation. • Planning scheme overlays protect biodiversity and reduce bushfire risk. • Fuel reduction burning and forest management actions consider individual species and ecosystem responses to fire regimes. • Fire management methods and technologies result in fewer, less intense and reduced area of bushfires. • Fire management practices and approaches consider cultural practices, biodiversity and protection of lives and property. • Public and private land managers set targets, actions and monitoring practices to maintain and improve native vegetation quality and whole ecosystem function. Pest plants and animals • Pest plant and animal control is well coordinated in local areas to ensure benefits are maximised, such as consistent and landscape-scale pest plant and animal management plans. • Develop a spatial prioritisation process for pest plant and animal control for local areas to ensure benefits are maximised. • Increased use of scientific research to underpin decision-making and investment in pest plant and animal control so that actions better address risks to biodiversity. • Increased funding for research agencies to develop new technologies and markets to control pest plants and animals. • The community and government is increasingly aware of the loss of biodiversity due to pest plants and animals. |

| Transforming | Increasing species diversity and habitat structures • The value of diverse vegetation and functioning ecosystems is acknowledged for cultural, carbon sequestration, health, intrinsic and economic reasons. • All land managers undertake stewardship actions to improve vegetation quality. • Planning overlays consider bushfire risk to humans, and restricts development in densely forested areas so they are managed for biodiversity rather than risk to life and property. • The revegetation industry is well-funded and continues to increase the diversity of plant species propagated and direct seeded. New techniques are developed that consider climate change impacts. • New technologies increase the resilience of biodiversity to climate change. • Funding is increased exponentially so that climate change effects on biodiversity are mitigated through targeted actions. • Cultural burning and other controlled burning practices are managed to benefit biodiversity, for example, promote germination, growth and recruitment of groundcover and understorey species, and can be effective at reducing fuel loads bushfire intensity. All controlled burning is within the regulations of CFA and DELWP fire plans and restrictions. • Revegetation plantings require consideration of bushfire risk to assets. Pest plants and animals • Introduced predators are eradicated and native predators are re-introduced. • New technologies are reducing the labour required to manage pest plants and animals and are more specific in their targets. • New technologies are eradicating pest plants and animals from high priority areas. |

Long-term outcome 3: Increase the area and diversity of native ecological communities permanently protected by 15,000 ha by 2040

Table 84: Priority actions required to help achieve long-term outcome 3

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established | • Covenants and other mechanisms (such as the carbon market) are delivered that result in long-term protection of native vegetation remnants. • Trust for Nature and other agencies work with landholders to secure permanent protection and ongoing management of high quality remnants that add to the National Reserve System. • Increase the area of land that is put into state and federal reserve systems. • Increase the frequency that non-governmental organisations purchase land for conservation management. • Expand opportunities for the carbon market and provide incentives for permanent protection. • Deliver cost-effective results using decision support tools in planning to help achieve and measure against the targets. • Renew the regional biodiversity implementation plan to coordinate action and investment across a range of partners. |

| Pathway | • Engagement in covenanting is increasing, and the community is aware of the values and obligations of covenants. • Individuals and corporations are investing in permanent protection through a range of mechanisms. • Governments are increasing investment in the National Reserve System through a range of mechanisms. |

| Transforming | • A mature biodiversity market is established to provide incentives for permanent protection of vegetation across the catchment. • Non-government organisations and the government have a clear long-term plan to purchase land to ensure all remaining EVCs are represented and flourishing in reserves despite climate change. |

Long-term outcome 4: Native vegetation provides linkages to allow the movement of species across and in 100% of priority landscapes by 2040

Table 85: Priority actions required to help achieve long-term outcome 4

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established | • Increase the quantity of revegetation in high value linkages across landscapes. • Research into the values of linkages is occurring and being communicated to stakeholders. • Public funds are used to create planted corridors more than 20 m in width. • Paddock tree projects are protecting large old trees, informing the community and growing new paddock trees as linkages. • Deliver cost-effective results utilising decision support tools in biodiversity planning processes to help achieve and measure against the targets. • Renew the regional biodiversity implementation plan to coordinate action and investment across a range of partners to increase native vegetation linkages. |

| Pathway | • Increased funding from a range of sectors is increasing the area of high value linkages across landscapes. • Community engagement is raising awareness and understanding of the importance of linkages in the landscape. • Research, particularly around the effects of climate change, is strengthening knowledge to protect, grow and enhance key linkages. • Influence local councils to strictly enforce development controls in high-value linkages areas to protect biodiversity and cultural heritage. • Build the catchment’s biodiversity plan into the local planning scheme and use it to guide the strategic protection, linking and regeneration activities in the context of the landscape and climate change. • Working in partnership with all land management sectors (aquatic and terrestrial) achieve a systems approach to decision-making and the best outcomes for biodiversity. • Identify, protect and enhance refugia to promote species persistence and ecosystem resilience to climate change. |

| Transforming | • The scale of revegetation and remnant protection is sufficient to create effective linkages across the landscape. • A variety of offset mechanisms that consider the protection of remnant vegetation and associated linkages. • Increase use of environmental water across waterways and wetland flows to provide drought refugia. • Connections to assist fauna to travel are abundant and assist fauna to re-establish in more suitable habitat as a result of climate change. |

Long-term outcome 5: Ten percent of 2021 identified threatened species and ecological communities are removed from the threatened species and ecological communities list by 2040

Table 86: Priority actions required to help achieve long-term outcome 5

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established | • Threatened species management includes targeted works for species, such as the mountain pygmy-possum, regent honeyeater and Euroa Guinea-flower. • Targeted projects in threatened species habitats and ecological communities result in multiple benefits for the catchment. • Threatened species are used to engage the public in biodiversity conservation. • The best available science is used to develop recovery plans. • The community is actively carrying out actions that reduce the risks to threatened species and climate change. • Deliver cost-effective results using decision support tools in planning to help achieve and measure against targets. • Renew the regional biodiversity implementation plan to coordinate action and investment across a range of partners to reduce the risks to threatened species and ecological communities. • Develop and adapt biodiversity strategies to reflect the latest scientific research. |

| Pathway | • Promote the urgency of action needed to save species and biodiversity as a priority on political and social agendas. • Increase funding to landscapes where works and increased knowledge will improve the extent and quality of habitat for a large number of threatened species and ecological communities. • Build an understanding of the impacts of climate change on threatened species and ecological communities. • Develop contingency plans for species most at risk of extinction from high risk events, such as cease to flow, drought and collapse of particular ecosystems due to bushfire and so on. • Identify the tipping points for the long-term viability of threatened species and ecological communities. • Investigate possible management options to influence the trajectory of threatened species and ecological communities in light of tipping points. |

| Transforming | • All land managers undertake stewardship actions to improve outcomes for threatened species and ecological communities. • Tipping points for threatened species and ecological communities are well understood and actions are in place to ensure long-term viability of species. |

Tracking progress

Monitoring outcomes

Progress towards the biodiversity theme outcomes will follow the strategy’s evaluation and adaptation framework outlined here.

Reporting condition

Catchment condition for the biodiversity theme will be reported annually through state-wide indicators, as part of the Goulburn Broken CMA Annual Report:

- native vegetation cover

- area of pest control

- area of weed control

- area of permanent protection.

Monitoring tipping points

Tipping points for the biodiversity critical attributes will be monitored where possible:

- native vegetation extent

- native vegetation quality

- landscape context

- threatened species.

References and further information

ANU (Australian National University) (2020) Ten ways to improve natural assets on a farm – ANU Sustainable Farms, Sustainable Farms, ANU.

Barr N (2018) Socio-economic indicators of change – Goulburn Broken and North East CMA Regions [PDF 21.31MB], Natural Decisions Pty Ltd.

Bennett AF (1999) Linkages in the landscape: the role of corridors and connectivity in wildlife conservation, IUCN Forest Conservation Programme, Australia.

Bennett A, Radford J and MacRaild L (2004) How much habitat is enough? Planning for wildlife conservation in rural landscapes, Land & Water Australia, Australian Government.

Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Victoria (2018) Victorian State of the Environment 2018 Report [PDF 20.01MB], Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Victoria, State Government of Victoria.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (2021) CAPAD: protected area data, DAWE, Australian Government.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (2021) Threatened Species Strategy 2021–2031, DAWE, Australian Government.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (2020) Indicative distributions of the nationally listed Threatened Ecological Communities, DAWE, Australian Government.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (2021) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act Threatened List, DELWP, State Government of Victoria.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (2019) Offsets for the removal of native vegetation, DELWP, State Government of Victoria.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (2017) Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037, DELWP, State Government of Victoria.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (2020) Victoria’s Land Cover Time series, DELWP, State Government of Victoria.

Goulburn Broken CMA (Catchment Management Authority) (2016) Biodiversity Strategy for the Goulburn Broken Catchment 2016-2021, Goulburn Broken CMA, Shepparton.

Goulburn Broken CMA (Catchment Management Authority) (2016) Revegetation Guide for the Goulburn Broken Catchment, Goulburn Broken CMA, Shepparton.

Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (2021) Protecting Victoria’s Biodiversity [PDF 10.83MB], Victorian Government Printer, Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Show your support

Pledge your support for the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy and its implementation.