Vision: Urban Centres offer employment, facilities and services for residents while valuing the natural environment.

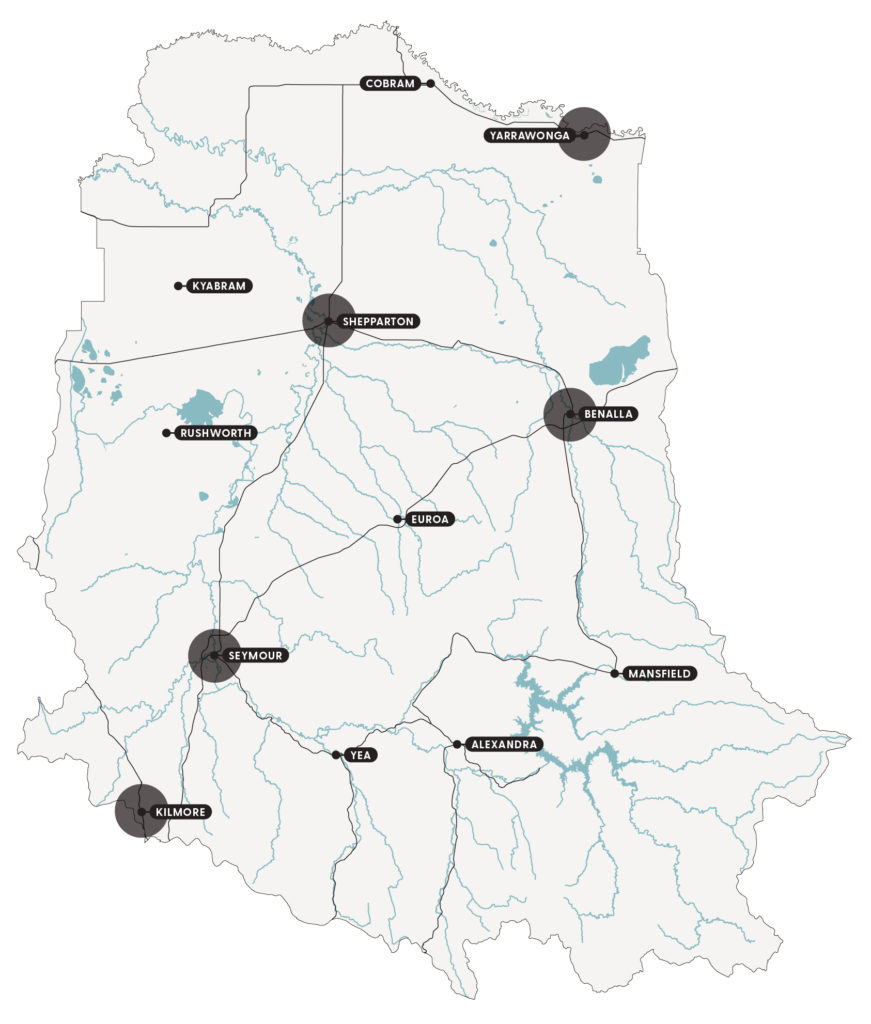

Urban Centres are the smallest sub-catchment system by area, but contain the largest populations (Figure 28). They are defined by a concentration of people, services and industries. The major urban centres are Shepparton, Seymour, Benalla, Kilmore and Yarrawonga.

The catchment’s abundant food and water resources were first enjoyed by the Yorta Yorta and Taungurung Clans and the many cultural sites in urban areas indicate the area’s importance to Traditional Owners.

The population living in urban centres has increased by 50% since 1981, with 74% of the total catchment population now living in a town, and a further 17% living in the urban fringe and dependent on towns for employment.

The growth has not been consistent across all towns with variation influenced by factors such as town size, planning constraints, proximity to water or hills, proximity to facilities and employment, dependence on industries with declining or growing employment and bushfires.

Towns are valued for the range of services and opportunities they offer such as employment, education, support, infrastructure, retail, healthcare and sporting.

Urban communities are very diverse and connected by employment, sporting and social groups, but may not be strongly connected to the natural environment. This connection is changing with developments capitalising on the natural environment and a growing number of people enjoying nature-based recreation.

Key features

A snapshot of the Urban Centres natural resources is provided under the themes of biodiversity, community, land and water.

Biodiversity

Some Urban Centres have major waterways and associated riparian and terrestrial habitat, such as large old hollow-bearing trees. The waterways provide native vegetation corridors through towns which can reduce the fragmentation of surrounding agricultural land by providing important linkages between remnants.

Urban Centres threaten biodiversity with high-density housing and associated infrastructure, cats and dogs, invasive species such as rats, foxes, Indian mynas and sparrows, inappropriately dumped garden waste and urban pollution.

Many areas are so ecologically degraded that they provide few ecosystem services other than land for housing, roads, businesses and other infrastructure. Native vegetation is scarce and highly fragmented, occurring mainly along the waterways. It is highly modified, generally in poor condition and managed more for recreational purposes by local government or Parks Victoria.

Community

Shepparton has a growing population, high workforce participation, residential migration and cultural diversity.

Between 1% and 3% of the population of many towns are First Nations people. Kinglake West has slightly higher proportion of between 2% and 4%, while in Shepparton and Murchison more than 4% of the population are First Nations people.

Murray irrigation towns that were dependent on dairy manufacturing have had declining employment since 2001. This is associated with changing dairy production due to drought, competition for water and international competition lowering milk prices.

Towns along the Murray River, or adjacent to a large water body, with growth-oriented planning schemes show consistent population and economic growth, such as Cobram, Yarrawonga and Nagambie.

Towns in economic proximity to Melbourne show strong growth, with increasing populations, larger households and construction industry employment, unless they have been impacted by bushfire, for example Kilmore, Broadford and Wandong, compared to Hazeldene.

Small towns show growth if they are in an attractive landscape and are close enough to a large town to function as a dormitory suburb, for example, Nagambie.

Small towns in the mixed-farming zone, generally south of Shepparton and north of the Hume Freeway, show structural ageing, smaller households and lower workforce participation. Retail, health and education are the main employers for towns such as Murchison, Euroa and Violet Town.

Population decline is more common in isolated towns such as Eildon, Thornton, Jamieson and Goughs Bay. Similarly, population decline is also happening in traditional agriculture or railway dependent towns, such as Colbinabbin, Rushworth, Girgarre, Stanhope, Merrigum and Glenrowan.

Towns of moderate size, such as Seymour and Benalla, also show long-term population decline. They have significant pockets of low income, falling income and structural ageing. Employment is in services for travellers, rather than tourism.

The impacts of the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires can be seen in population decline in Marysville and Kinglake.

Land

Intensive housing, business facilities and supporting infrastructure are typical land uses. Centres are often surrounded by lifestyle or agricultural properties, industrial enterprises and some public parks and forests, particularly along waterways.

The current condition of land and soil health is poor. Soil health is threatened by erosion, organic matter decline, contamination, compaction and biodiversity decline related to land use.

Water

Waterways and wetlands are a major feature and valued for their aesthetic appeal and the recreation and economic services they provide.

Many waterways are under stress from threats associated with higher density living, such as gross and diffuse pollutants, flood mitigation works that change flows, aquatic weeds and European carp.

The area’s waterways have been highly modified to accommodate development and infrastructure. Water is extracted from regulated and unregulated rivers, lakes and groundwater for household and industry use, with waste and stormwater discharged back into the waterways. Wastewater is treated prior to discharge, but often stormwater is not. Any pollutants change the chemistry of the water which affects fish and their food.

Current condition

Community and stakeholder engagement over the past 6 years has identified 4 critical attributes that are fundamental to the character of the Urban Centres:

- business, education and employment

- water

- natural environment

- community.

The current condition and trends for each attribute are outlined in Table 63.

They have been drawn from Goulburn Broken CMA annual reports, tipping points described by the community, socio-economic research and the water, land and biodiversity theme papers developed as part of the strategy renewal.

Table 63: A snapshot of current condition and trends for the critical attributes of the Urban Centres

| Critical attribute | Description | Current condition* | Trend** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business, education and employment | • Provides employment opportunities. • Provides business opportunities. • Access to public transport and other towns. | Pressures to adapt and transform the economy means the condition varies – good to poor condition. Ability to absorb, respond, recover and renew – stable. | Adaptation and transformation phase. |

| Water | • Access to reliable, good quality potable water in the home and when out, such as bubble taps. • Attractive water assets for recreational values and aesthetics. • Water and fish in the rivers, creeks, lakes and reservoirs. | Urban water supplies – good condition. Surface water systems – moderate condition. Ability to absorb, respond, recover and renew – under pressure. | Adaptation phase. |

| Natural environment | • Creating an attractive environment, with high liveability, greening strategies and heat protection. • Safe from bushfires and prepared for emergencies such as floods. | Conservation reserves are too few and small, with a high impact from introduced species – poor condition. Ability to absorb, respond or recover and renew – limited. | Transformation phase. |

| Community | • Connection to a range of employment, education and lifestyle opportunities and services. • A sense of belonging and connection. • Health and wellbeing. • Liveability. | Physical and digital connections – moderate condition Ability to absorb, respond, recover and renew – under pressure. | Adaptation and transformation phase. |

**The trend refers to resilience phase and/or type of change the critical attribute is experiencing generally, such as persistence, adaptation or transformation.

Drivers of change

Tables 64-67 outline the 4 major drivers of change impacting Urban Centres and what they mean for the critical attributes:

- climate change

- transition to a services economy

- technological development

- acute system shocks.

The drivers of change were identified through community engagement and socio-economic analysis as part of the strategy renewal.

Driver 1: Climate change

Table 64: The impacts of climate change and what they may mean for the Urban Centres critical attributes

| Impacts | What climate change may mean for the critical attributes |

|---|---|

| • A hotter and drier climate. • Reduced reliability of rainfall in spring and autumn. • Increased frequency and intensity of storms, heatwaves, bushfires and droughts. • Longer and more severe periods of drought. • Increased frequency and severity of bushfires. | Business, education and employment • Frequency of natural disasters exhausts the community’s financial, physical and emotional resources to prepare, recover and grow. Water • Climate variability, reduced recharge and over extraction threaten larger groundwater aquifer assets. • Threatened amenity and recreation values of native vegetation, rivers, streams and lakes. • Increasing demand and competition for water, for example, for recreation. • Increasing risk of water quality issues such as blackwater and blue-green algae. Natural environment • Threatened amenity and recreation values of native vegetation, rivers, streams and lakes. • Opportunity for greening of urban centres and connection to natural environments, such as rivers. Community • Threatened amenity and recreation values of native vegetation, rivers, streams and lakes. • Increasing interest in solar power and batteries. • Desire for more greenery and access to parks. • Need for safe community places for emergency access. • Increasing demand on heating and cooling. • Demand for ecologically sustainable design and appropriate planning. • Desire for carbon neutrality. |

Driver 2: Transition to a services economy

Table 65: The impacts of a transition to a services economy and what they may mean fo the Urban Centres critical attributes

| Impacts | What a transition to a services economy may mean for the critical attributes |

|---|---|

| • Increasing population growth. • Urban population growth. • Increased demand for lifestyle properties close to towns. • Increased rural land prices where there is demand for lifestyle properties in high amenity areas, such as Nagambie, and areas close to towns, such as Benalla. • Increasing urban incomes create demand for recreation and amenity experiences. • Government funding priorities shifting away from agriculture and NRM. | Business, education and employment • Major employment in education, health, retail and manufacturing, with employment in agriculture decreasing. • Increasing gap between educational levels and employment opportunities. Water • Increasing visitation and poor management threatens amenity and recreation values of native vegetation, rivers, streams and lakes. Natural environment • Increasing visitation and land clearing threatens the amenity and recreation value of native vegetation. • Need for consideration of changing amenity in planning, such as an ecologically sustainable design. Community • Population increasingly values the natural environment for an enhanced lifestyle, rather than for earning a living. |

Driver 3: Technology development

Table 66: The impacts of technology development and what they may mean for the Urban Centres critical attributes

| Impacts | What technology development may mean for the critical attributes |

|---|---|

| • Allows more people to work from home or away from major cities. • Facilitates the emergence of online businesses. • Social media provides a platform for communication. | Business, education and employment • Potential for increased business and employment opportunities. • Changing business types, such as fewer shop fronts. • Increasing demand and prices for housing and lifestyle properties. Water • Potential for increased innovation in water recycling and management. Community • Potential to connect with volunteers online. • Potential to connect with visitors in new ways. |

Driver 4: Acute system shocks

Table 67: The impacts of acute system shocks and what they may mean for the Urban Centres critical attributes

| Impacts | What acute system shocks may mean for the critical attributes |

|---|---|

| • Increasing extent, intensity and unpredictability of natural disasters, such as bushfires and droughts. • Pandemics, such as COVID-19. • International or policy driven downturns in industries, such as the Global Financial Crisis. | Business, education and employment • Extent of natural disasters exhausts the community’s financial, physical and emotional resources to prepare, recover and grow. • Impact on accommodation, food services, arts and recreation industries, and on towns that depend on these industries. • Downturns in industries resulting in declining town populations. Water • Potential for reduced water quality, such as reduced oxygen, black water and blue-green algae events. Natural environment • Native vegetation is seen as a threat to safety, from bushfires and wildlife, so there is pressure to clear or replace it. Community • Increased diversity of people living in the area. • Increased connection to local nature-based recreation reserves and paths. |

Tipping points

Understanding and identifying tipping points of significant change is important to increasing the resilience of the Urban Centres and their important social, economic and environmental services.

Significant change occurs when the characteristics of a system change so much that the system is no longer the same. Some tipping points are well-understood and can be used to guide management, while others are still being understood.

Planning with local communities over the last 6 years has identified tipping points for the critical attributes for the local area. They are presented in Table 68. The strategy provides an opportunity to identify and further test tipping points.

Table 68: Community tipping points for the Urban Centres critical attributes

| Critical attribute | Community tipping point |

|---|---|

| Business, education and employment | • Education levels. • Employment levels. • Liveability surveys, such as regional well-being survey. |

| Water | • Temperature, turbidity, yield, black water and blue-green algae events. • Water does not meet demand and it is not fit-for-purpose. • Access to water and level of water use on a per person average. |

| Natural environment | • Local extinctions and a reduction in extent and diversity. • Community connection to nature. • Volunteering. |

| Community | • An increased difficulty in dealing with change when population increases. • Town and rural planning issues. • School closures. • Level of mental health issues. • Connection to community. • Availability of resources, such as halls, recreation and paths. |

Community vision and outcomes

Community and stakeholder engagement over the past 6 years has helped develop the following vision and outcomes for the Urban Centres. The outcomes focus on what needs to happen given the impacts of the drivers of change. Specific priority actions have been described to achieve the outcomes.

Please note, the outcomes are not in priority order. All 4 outcomes are equally important and complementary. Consideration of all outcomes is required during implementation to achieve the vision.

Vision

Urban Centres offer employment, facilities and services for residents while valuing the natural environment.

Outcomes

- The economy is adapting to change, ensuring native vegetation, water, economy and community critical attributes remain below the tipping points.

- Local improvement in the diversity, extent and connection of biodiversity.

- The community is cohesive, collaborative and connected to nature.

- The community understands the impact of actions and how to ensure native vegetation, water, economy and community critical attributes remain below tipping points.

Priority actions

Priority actions for the Urban Centres have been identified for each of the 4 outcomes (Tables 69-72). They provide ideas and options for the future, rather than fixed work plans. The actions must evolve as the catchment changes and new information becomes available.

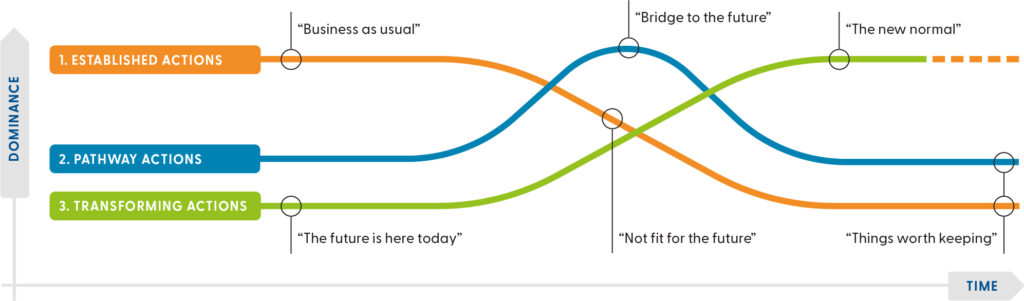

The tables present priority actions for each outcome as:

- Established actions, which are those currently happening that we would like to continue. They include business as usual, recognised and existing practices. These are actions that are widespread and well-understood.

- Pathway actions, which are innovations that help shift from the current situation to an ideal future. For example experiments, bridging or transition actions that take place during the transition from established to transforming actions.

- Transforming actions, which are the way things could work in the future. For example, the new normal, visionary ideas and new ways of doing things to create change. There may be pockets of these already happening.

A combination of all 3 types of actions is required to achieve the vision for the future (Figure 29).

Dividing actions this way is based on the Three Horizons framework and helps communities:

- think and plan for the longer-term by identifying emerging trends that might shape the future

- understand why current practices might not lead to a desired future

- recognise visionary actions that might be needed to get closer to a desired future.

Outcome 1: The economy is adapting to change, ensuring native vegetation, water, economy, and community critical attributes remain below the tipping points

Table 69: Priority actions for outcome 1

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established actions | • Build awareness of opportunities to transition to new industries, such as renewable energy, tourism and specialised manufacturing, that are able to adapt to system shocks. |

| Pathway actions | • Strengthen the regional planning policies and compliance to keep critical attributes below the tipping points. • Build nature-based tourism and recreation opportunities. • Effectively plan for long-term use of Urban Centres and build an understanding of future businesses, services and careers by matching them with towns that are relevant given potential climate scenarios. |

| Transforming actions | • A regional carbon credit initiative is trialled that enables urban people, including visitors, to offset their climate change impacts and contribute to funds for rural land managers to use in regenerating biodiversity, native vegetation and soil health. |

Outcome 2: Local improvement in the diversity, extent and connection of biodiversity

Table 70: Priority actions for outcome 2

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established actions | • Increase awareness of urban options to build and protect biodiversity. • Strengthen urban initiatives to protect and build biodiversity in parks, streets and waterways on public and private land. • Strengthen urban initiatives to reduce the spread of garden weeds and the impact of domestic pets. • Connect the urban community to the environment by planning and implementing water management concepts such as the development of artificial wetlands, river paths and treatment opportunities. |

| Pathway actions | • Nurseries and councils provide and use species and advice that support biodiversity and are resilient to climate change. • Identify and support methods to increase urban ecology. • Quantify and build awareness of the increased economic, lifestyle and health benefits of native vegetation. |

| Transforming actions | • Increased percentage of climate appropriate provenance and species that provide shade are required in developments and parklands. • Visitors and urban communities pay for and actively seek opportunities to reduce impacts on the environment when visiting public land. |

Outcome 3: The community is cohesive, collaborative and connected to nature

Table 71: Priority actions for outcome 3

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established actions | • Build an understanding of resilience and capacities to predict, respond and recover from acute system shocks. • Create opportunities for joint discussions and sharing of information and program design between groups such as the CMA, Landcare and local government. • Strengthen the range of information and resources available for urban populations to build an understanding and connection to the environment. • Increase the involvement of Traditional Owners in urban planning and initiatives. • Grow the links and understanding between community health and the environment. • Build community respect and support for Traditional Owners’ knowledge, culture and values. |

| Pathway actions | • Build online infrastructure to create inclusive networks, build access and share information. • Create volunteer opportunities for residents and visitors to the region. • Broaden governance, communication and links to include groups such as sporting and schools. • Grow opportunities for citizen science to increase the connection and understanding of recreational areas. • Increase the focus on developing young people’s connection to nature through schools, sporting and recreation groups. • Greater inclusion and interest in Traditional Owners’ ecological knowledge and First Nations culture. |

| Transforming actions | • A stewardship approach unites groups, sectors, industries and initiatives that use, manage, resource or care for natural resources. • Community planning responds to potential scenarios. • Traditional Owner knowledge and perspectives are included in urban strategic plans and implementation. |

Outcome 4: The community understands the impact of actions and how to ensure native vegetation, water, economy and community critical attributes remain below tipping points

Table 72: Priority actions for outcome 4

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established actions | • Include natural resource opportunities about obligations and groups to get involved with, in information and welcome packs for new residents. • Build the private sector’s understanding of the impacts of different actions on the area’s critical attributes. |

| Pathway actions | • Develop tools that quantify, measure and monitor the impact of land use, management practices and recreational activities on the critical attributes. • Build community acceptance of contributing to the management and repair of natural areas that are visited and used. |

| Transforming actions | • Strengthen regional planning policies and compliance to keep the critical attributes below the tipping points. • Introduce user pays fees for active and passive use of the natural resources. • Community members and visitors make stewardship payments to public and private land managers to offset their environmental impacts and contribute funds for use in NRM projects. |

References and further information

Barr N (2018) Socio-economic indicators of change – Goulburn Broken and North East CMA Regions [PDF 21.31MB], Natural Decisions Pty Ltd.

Benalla Rural City (2020) Council Plan 2017-2021 (2020 Review) [PDF 26MB], Benalla Rural City, Benalla.

Campaspe Shire Council (2016) Council Plan 2021-2026 [PDF 12.92MB], Campaspe Shire Council, Kyabram.

Greater Shepparton City Council (2016) Council Plan 2017-2021, Greater Shepparton City Council.

Mansfield Shire Council (2016) Council Plan 2017-2021, Mansfield Shire Council, Mansfield.

Mitchell Shire Council (2016) Council_Plan_2017-2021 [PDF 1.73MB], Mitchell Shire Council, Broadford.

Moira Shire Council (2016) Council Plan 2017-2021, Moira Shire Council, Cobram.

Murrindindi Shire Council (2016) Council Plans 2017-2021, Murrindindi Shire Council, Alexandra.

Strathbogie Shire Council (2016) Council Plan 2017-2021, Strathbogie Shire Council, Euroa.

Show your support

Pledge your support for the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy and its implementation.