Vision: With the community, the Southern Forests balances ecological, economic, cultural and recreation needs to preserve natural resource health.

The Southern Forests local area in the catchment’s south and south-east includes seasonally snow-covered alps, moist montane and sclerophyll forests (Figure 26).

The Taungurung were the first people of this area and have on-going land management responsibilities through the Recognition and Settlement Agreement between the Taungurung Land and Waters Council Aboriginal Corporation, the Taungurung Traditional Owner group, and the state government.

Public land is managed as state forest, alpine resorts and national or state parks by Taungurung Land and Waters Council, Parks Victoria, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, the Alpine Resorts Co-ordinating Council and Alpine Resort Management Boards.

This public land has the largest intact native vegetation areas in the catchment.

Over the past 100 years, the area has been shaped by events such as bushfires, gold rushes and post-war timber industry development. In recent years, the concentration of timber mills has fallen, while tourism demands have increased.

The natural resources are used for forest reserve, recreation, tourism, hydropower, water capture and storage and production forestry, including native forests and plantations. These require supporting infrastructure including roads and telecommunication.

The forest landscapes are highly valued for their ecological extent and diversity, cultural significance and economic contribution from recreation, tourism, plantation and native forest timber harvesting. Soils are fragile and often on steep slopes. The ecosystem services include high-quality and reliable water that provide environmental, economic and social value.

Key features

A snapshot of the Southern Forests natural resources is provided under the themes of biodiversity, community, land and water.

Biodiversity

From the valleys to the mountains, old growth damp and wet forests, interspersed with rainforests, give way to mixed species forest of peppermints and box trees. High on the slopes, snow gum woodlands dominate a herb-rich ground layer. Above the snowline, unique fens and bogs are alive with frogs and water nymphs. The large forests contain unique vegetation including Alpine Sphagnum Bogs, fens and habitat such as boulder fields.

The unique vegetation, fauna communities and species include the Alpine frog, groundwater dependent ecosystems, peat bogs and wetlands. Endangered Vegetation Communities (EVCs) include sub-alpine and montane grasslands, shrublands or woodlands, with rare EVCs including Alpine rocky outcrops and sub-Alpine dry shrubland.

Threatened species and communities include the mountain pygmy possum and frogs such as Dendy’s toadlet, spotted tree frog, which is critically endangered in Victoria and endangered nationally, growling grass frog, brown toadlet, which is endangered in Victoria, and the Alpine tree frog, which is critically endangered in Victoria and vulnerable nationally. Barred galaxias are endemic to the region, and endangered, and the cool temperate rainforest EVC is endangered.

Community

Many Taungurung people continue to live on Country and, with Taungurung that live elsewhere, are active in the protection and preservation of culture, land, and waters.

People pursue a range of recreational activities, including skiing in winter, fishing, bush walking, driving, cycling, and camping. Recreation and tourism contribute economic wealth to the area.

Some small communities are permanent. Seasonal communities service the recreation and tourism industries, forest harvesting activities and the maintenance of infrastructure that supports them.

In addition, there are high numbers of lifestyle properties that people visit for holidays and weekends. This means the community is often not connected to each other or the surrounding environment.

Land

The terrain is characterised by mountains and relatively narrow valleys. They are predominantly formed from sedimentary rocks, some metamorphosed, with some granite intrusions. The dominant soil types are chromosols, kurosols and dermosols. These can be highly erosive due to terrain and/or soil physical and chemical properties and highly acidic.

Water

The area contributes to healthy river ecosystems, providing reliable, filtered high-quality water, although there is mercury contamination in some waterways from past mining.

Priority waterways assets are:

- Goulburn River, in which the upper, ecologically healthy reach of this heritage river supports many threatened species including the barred galaxias, spotted tree frog and Alpine bent.

- Rubicon River, which is a priority river with near ecologically healthy status. It supports barred galaxias in the tributary streams of the Keppel Hut Creek, Pheasant Creek, Perkins Creek, Taggerty River, Torbreck River and Stanleys Creek.

- Big River, which is a heritage river containing ecologically healthy and representative reaches that support the threatened spotted tree frog.

- Howqua River, which is a heritage river that has high economic value in the form of tourism and recreation.

The current condition of wetlands in the area is good. Major threats are pest plant and animal invasion and soil erosion.

Priority wetland assets include:

- Alpine bogs, which are areas that protect the nationally endangered Alpine sphagnum bogs and associated fens ecological community.

- Central Highlands Peatlands, which includes 5 separate sphagnum moss dominated bogs located along rivers and gullies.

Current condition

Most of the land in the Southern Forests is publicly owned and managed, including significant areas owned by the Taungurung Land and Waters Council. A review of the public management strategic plans has identified 4 critical attributes that are fundamental to the character of the Southern Forests:

- economy

- water

- native vegetation and wildlife

- heritage.

The current condition and trends for each attribute are outlined in Table 54.

Table 54: A snapshot of current condition and trends for the critical attributes of the Southern Forests

| Critical attribute | Description | Current condition* | Trend** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economy | • Snow and non-snow-based tourism. • Recreational use. • Forestry. | Pressure to adapt and transform the economy means the condition varies – good to poor condition. Ability to absorb, respond, recover and renew – under pressure. | Adaptation and transformation phase. |

| Water | • Temperature, turbidity and yield. • Rainfall. • Catchment and rivers. | Surface water systems – good to excellent condition. Ability to absorb, respond, recover and renew – fair. | Persistence and adaptation phase. |

| Native vegetation and wildlife | • Extent and quality. • Flora and fauna. • Land and aquatic based. • Intact unique environment. • Amenity. | Extensive areas of public forest – good condition. Ability to absorb, respond, recover and renew – fair. | Persistence and adaptation phase. |

| Heritage | • Aboriginal. • Non-indigenous. | Knowledge of aboriginal and non-indigenous cultural heritage is being lost with an ageing population and the small number of Taungurung peoples able to live and work on Country – poor condition. Ability to absorb, respond, recover and renew – under pressure. | Adaptation and transformation phase. |

**The trend refers to resilience phase and/or type of change the critical attribute is experiencing generally, such as persistence, adaptation or transformation.

Drivers of change

Tables 55-58 describe the 4 major drivers of change impacting the Southern Forests and what they means for the area’s critical attributes:

- climate change

- increased tourism and recreation

- increasing and competing priorities for public resources and changes to public policy

- increasing number and extent of pest plants and animals.

The drivers of change were identified through community engagement and socio-economic analysis as part of the strategy renewal.

Driver 1: Climate change

Table 55: The impacts of climate change and what they may mean for the Southern Forests critical attributes

| Impacts | What climate change may mean for the critical attributes |

|---|---|

| • A hotter and drier climate. • Reducing reliability of rainfall in spring and autumn. • Increasing the frequency, intensity and extent of bushfires. | Economy • Declining snow-based tourism and recreation and a transition to non-snow-based tourism and recreation, such as mountain biking. • Reduced access for summer-based activities, such as hiking and camping, because of the threat of bushfires. • Changes to the suitability of forestry species. Water • Increase in stream temperatures impacting vulnerable species. • Reduced run-off, associated with reduced rainfall or forest regrowth after bushfires, impacting stream flows, quality, water yield and supply to local and downstream communities. • Decline in Alpine bogs. • Decreased water quality from erosion following bushfires. • Increased flooding, erosion and damage to roads from intense rainfall events. Native vegetation and wildlife • Increased frequency of fire threatening vulnerable species and EVCs. • Increased fires impacting species differently and resulting in more homogeneous forests. • Increasing rate of decline of the vulnerable Alpine native flora and fauna. Cultural heritage • Potential loss of cultural heritage due to fires and erosion after heavy rainfall. |

Driver 2: Increased tourism and recreation

Table 56: The impacts of increased tourism and recreation and what they may mean for the Southern Forests critical attributes

| Impacts | What increased tourism and recreation may mean for the critical attributes |

|---|---|

| • Increased population and development. • Increased demand for services and facilities. • Increased damage to sealed and unsealed roads. • Increased interactions with the area, increasing its value. | Economy • Economic growth of tourism and recreation businesses and employment. • Increased demand for improved access to areas. • Increased management of impacts from concentrated visitation. Water • Increase the interest of anglers to help improve river health. • Increases in biological pollution in river systems, such as E. coli. • Increased demand for drinking water. • Increased extraction from local streams. Native vegetation and wildlife • Greater difficulty controlling pest animals and plants, such as foxes and weed infestations, in areas with more lifestyle properties. • Increasing number of domestic animals moving into the forests, such as cats and dogs. • Increased maintenance required for walking tracks, camping areas and streams. • Increased erosion due to damage from four-wheel drives on steep and erodible sites. • Impacts on native vegetation and wildlife becoming secondary to economic development, such as snow making dams. Heritage • Development putting pressure on cultural heritage sites. • More tourism opportunities to protect cultural heritage sites. |

Driver 3: Increasing and competing priorities for public resources and changes to public policy

Table 57: The impacts of increasing and competing priorities for public resources and changes to public policy and what they may mean for the Southern Forests critical attributes

| Impacts | What the increasing and competing priorities for public resources and changes to public policy may mean for the critical attributes |

|---|---|

| • Urgent and large-scale changes are identified for the region to improve NRM and adapt to climate change (such as manage bushfire risk). • Changing approaches to bushfire management and response. • Changes to forestry agreements. • Traditional Owner Settlement Agreements. | Economy • A transitioning forestry industry. • Increasing demand for new investment and volunteering opportunities on public land to meet the urgent and large-scale changes required to improve NRM. Water • Decreased water quality following rainfall events from erosion and runoff from areas of increased logging. Native vegetation and wildlife • Declining quality of native vegetation due to grazing pest animals and weeds. • Increasing impact of the logging of old growth forests due to major events such as bushfires. • Threats to alpine species due to uncontrolled bushfires. • Increased involvement of Traditional Owners in bushfire management decisions and practices. • Broader range of bushfire management approaches and responses available. Heritage • Increased Traditional Owner-led cultural heritage protection and management. |

Driver 4: Increasing number and extent of pest animals and plants

Table 58: The impacts of an increasing number and extent of pest animals and plants and what they may mean for the Southern Forests critical attributes

| Impacts | What an increasing number and extent of pests may mean for the critical attributes |

|---|---|

| • Increasing populations of pest grazing animals particularly deer, feral horses and pigs. • Increasing populations of predatory animals, such as foxes and cats. • Increasing weed populations. | Economy • Increased risk on roads from deer and feral horses. • Increasing cost of protecting native vegetation from pest grazing animals. Water • Increase turbidity and biological contamination of water. Native vegetation and wildlife • Decline in plant communities due to grazing pressure from pigs and deer. • Decline in small mammals due to increased predation by foxes and feral cats. • Increases in weed species such as holly and blackberry. Heritage • Pugging and general damage to the culturally significant Alpine bogs and waterways by feral deer and pigs. |

Tipping points

Understanding and identifying tipping points of significant change is important to increasing the resilience of the Southern Forests and its important social, economic and environmental services.

Significant change occurs when the characteristics of a system change so much that the system is no longer the same. Some tipping points are well-understood and can be used to guide management, while others are still being understood.

Planning with local communities over the last 6 years has identified tipping points for critical attributes for the local area. They are presented in Table 59. The strategy provides an opportunity to identify and further test tipping points.

Table 59: Community tipping points for the Southern Forests critical attributes

| Critical attribute | Community tipping point |

|---|---|

| Economy | • Snow and non-snow related tourism. • Forestry. |

| Water | • Temperature, turbidity and yield. • Potable water supplies for towns. |

| Native vegetation and wildlife | • Biodiversity and native vegetation keystone species. • Reduced extent of high priority landscapes. |

| Heritage | • Increased difficulty in retaining cultural heritage with changing and increasing population. • Town and rural planning issues, as development impacts cultural heritage. |

Community vision and outcomes

The Southern Forests local area vision and outcomes were developed with a focus on natural resources and to integrate key values detailed in the Taungurung Country Plan and other public land managers’ strategic plans.

Please note, the outcomes are not in priority order. All 3 outcomes are equally important and complementary. Consideration of all outcomes is required during implementation to achieve the vision.

Vision

With the community, the Southern Forests balances ecological, economic, cultural and recreation needs to preserve natural resource health.

Outcomes

- The economy is supported to adapt to climate change.

- New developments and increasing visitor access improves diversity, extent and connection of native vegetation and wildlife.

- The community is cohesive, connected and collaborative.

Priority actions

Priority actions for the Southern Forests have been identified for each of the 3 outcomes (Tables 60-62). They provide ideas and options for the future, rather than fixed work plans. The actions must evolve as the catchment changes and new information becomes available.

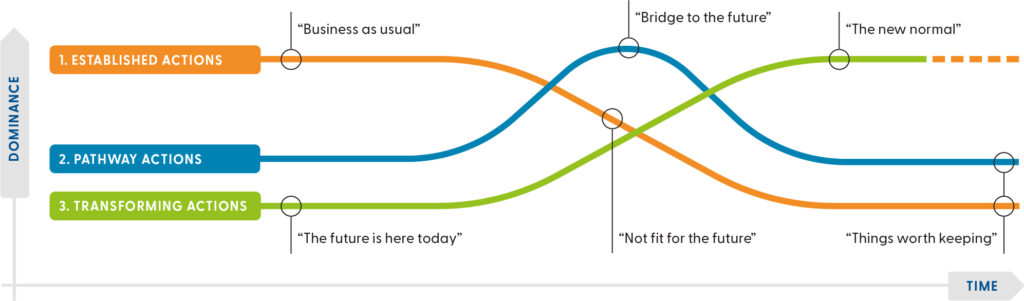

The tables present priority actions for each outcome as:

- Established actions, which are those currently happening that we would like to continue, such as business as usual, recognised and existing practices. These are actions that are widespread and well-understood.

- Pathway actions, which are innovations that help shift from the current situation to an ideal future, such as experiments, bridging or transition actions that take place during the transition from established to transforming actions.

- Transforming actions, which are the way things could work in the future, such as the new normal, visionary ideas and new ways of doing things to create change. There may be pockets of these already happening.

A combination of all 3 types of actions is required to achieve the vision for the future (Figure 27).

Dividing actions this way is based on the Three Horizons framework and helps communities:

- think and plan for the longer-term by identifying emerging trends that might shape the future

- understand why current practices might not lead to a desired future

- recognise visionary actions that might be needed to get closer to a desired future.

Outcome 1: The economy is supported to adapt to climate change

Table 60: Priority actions for outcome 1

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established actions | • Enhance the visitor experience, develop and diversify resorts with a light footprint. • Increase support for ethical economic development and employment for Taungurung people and Country. • Increase awareness and dialogue with stakeholders, who get an income from the area, on climate change impacts on water and native vegetation, the risks and adaptation options. • Planned burning and other fuel reduction measures take access into account. |

| Pathway actions | • Investigate forestry adaptation options such as alternatives to clear felling, seedling regeneration, thinning to reduce water stress, new species and genotypes for public and private forests. • Include changes to climate, risk and populations in planning and management. • Integrate local community knowledge of past and current changes in management plans. • Quantify the economic value, costs of access and use of native vegetation and water bodies, and integrate them in decision making processes and tools. |

| Transforming actions | • Diversified local and regional economies that account for the change in climate and integrate ecological and social costs and benefits. • Support investment from the private sector in native vegetation management and improvements with trusted metrics and tools. |

Outcome 2: New developments and increasing visitor access improves diversity, extent and connection of native vegetation and wildlife

Table 61: Priority actions for outcome 2

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established actions | • Strengthen the control of feral grazing and predatory animals, including horses, foxes, dogs and cats. • Strengthen the implementation of a coordinated, inclusive program of deer management and control. • Targeted weed containment and landscape management for species such as broom, blackberries, willows and Chilean needle grass. • Increase roadside prohibited weed and rabbit management programs and roadside conservation and erosion control by training contractors, mapping and applying strategies. • Implement and maintain stream buffers, building on current interest from anglers to protect water quality and biodiversity. • Increase the speed of re-forestation after bushfire and timber harvesting. • Strengthen public land management to repair and prevent the loss of biodiversity. • Implement management practices to secure populations of recreational species and native fish, for example, riparian revegetation, fish sanctuaries, stocking and translocation. • Describe the impact of a range of climate scenarios on native flora and fauna and match the Southern Forests to areas with those climate regimes. • Renew the regional biodiversity implementation plan to coordinate action and investment across a range of partners to increase native vegetation extent. • Implementation of the Victorian Forestry Plan to phase out all native timber harvesting by 2030, while supporting workers, businesses and communities. • Creation of Immediate Protection Areas (e.g. the Strathbogie Ranges), additional protections for old growth forests and improved management of Victoria’s forest to protect remnant vegetation (e.g. review of the code of forest practice for timber harvesting, major event review of regional forest agreements). |

| Pathway actions | • Support the community to understand and embrace the provenance shift that is occurring due to climate change. • Quantify the value of protecting and improving native vegetation, such as carbon, health and economic value, and integrate in decision making tools. • Support the development of a user pays system for native vegetation and wildlife, for recreation and business purposes, that funds management and rehabilitation. • Build awareness of the increased value of native vegetation on things such as carbon, economic, lifestyle, health and species persistence benefits. • Strengthen the regional planning policy and compliance to permanently protect priority native vegetation with appropriate planning decisions and public land management practices. • Bushfire management and planning is transparent and inclusive and integrates the protection and enhancement of ecosystems. • Increase the understanding of the likely change in vegetation extent due to climate change. • Broaden revegetation options, provenance and practices to ensure they support the flexibility needed to adapt to changes in climate policies and population. • The value of biodiversity on public land is quantified and integrated in planning and management decisions. |

| Transforming actions | • Support investment from the private sector in native vegetation management and improvements with trusted metrics and tools. • Effective implementation of a mix of regulation, compliance, incentives and education targeted at the diverse range of users and land managers. • Priority native vegetation on private and public land is protected and compliance is ensured within the agreed tipping points. • Visitors and communities pay for and reduce their impact on the environment when visiting public land. • Land managers receive payment from users of native vegetation. • Benefits of native vegetation are built into economic decisions. • Biodiversity planning and implementation decisions are resilient under the future climate scenarios. • Traditional ecological knowledge guides management practices on public and private land. |

Outcome 3: The community is cohesive, connected and collaborative

Table 62: Priority actions for outcome 3

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established actions | • Build and strengthen partnerships with Taungurung people across policy, planning and delivery. • Build capacity of agency partners and Traditional Owners to engage in partnerships with shared priorities and outcomes. • Build community respect and support for Taungurung people as guardians of Taungurung Country. • Increase access to information and services for tourists and recreational users to support the sustainable use of the environment. • Encourage angler behaviour that improves post-release survival. • Increase connections, understanding and collaborations with the key industries that impact biodiversity, such as tourism, mining and logging. |

| Pathway actions | • Greater inclusion and interest in Traditional Owners’ ecological knowledge and First Nations culture. • Greater employment of Taungurung people in organisations that manage local land and water. • Strengthen connections between visitors and weekenders to the area, and provide opportunities to make a positive difference to the environment. • Work with CFA to discuss and implement fuel management activities with a focus on cultural practices, biodiversity and protection of lives and property. |

| Transforming actions | • Traditional Owner-led land management decision making and implementation. • Environmental stewardship* is embraced by the community, including visitors, and leads to collaboration between diverse groups and sectors that use, manage, fund or care for the natural resources. • Urban community members and visitors make stewardship payments to public and private land managers to offset their environmental impact, and contribute funds for use in NRM projects. |

References and further information

Barr N (2018) Socio-economic indicators of change – Goulburn Broken and North East CMA Regions [PDF 21.31MB], Natural Decisions Pty Ltd.

Mansfield Shire Council (2016) Council Plan 2017-2021, Mansfield Shire Council, Mansfield.

Murrindindi Shire Council (2016) Council Plans 2017-2021, Murrindindi Shire Council, Alexandra.

Goulburn Broken CMA (Catchment Management Authority) (n.d.) Southern Forests SES Local Plan [PDF 712.47KB] Goulburn Broken CMA, Shepparton.

Show your support

Pledge your support for the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy and its implementation.