Vision: A motivated and connected community leads positive change for people, land, water and biodiversity.

Community capacity and resilience are closely linked to the health of the catchment’s natural resources. The Goulburn Broken Catchment community has long been involved in the management of natural resources and continued buy-in is essential to achieve the large-scale, urgent and complex change needed to improve natural resource health and respond to climate change.

There are a number of drivers and trends influencing community capacity, resilience and involvement in NRM. Firstly, the people using and influencing the catchment’s natural resources are increasingly diverse, with many living outside the catchment. In addition, the majority of the catchment’s population now live and work in urban centres and towns with the transition to a service economy. This has resulted in residents increasingly valuing the natural environment to enhance their lifestyle, rather than for earning a living, similar to the large number of visitors who come for recreational activities such as fishing, camping and skiing.

Adding to the complexity, the people managing natural resources are not always the same as those using or benefitting from them. The catchment’s natural resources may be managed publicly, by government and Traditional Owners, and/or privately, by farmers and lifestyle landholders, with differences in management approaches and values. For example, much of the private land is managed for agricultural production, and while NRM is critical to the sustainability of agricultural businesses (private benefit), it also provides a lot of benefit for the community and environment (public benefit).

With changes in the catchment population and the increasing diversity and complexity between natural resource users and managers, community engagement in NRM is changing. Furthermore, with increasing and competing priorities for public resources, combined with the urgency to improve the catchment’s natural resources, the demands on community volunteers are increasing along with the need to explore new investment opportunities and engagement models.

A snapshot of the community theme of the strategy is provided in Figure 37, click on the tabs below for further details.

Background

Values

The catchment community is becoming increasingly diverse, with growing urban and lifestyle populations. The number of people visiting for recreation and weekends away is also increasing. This diversity means that how people value natural resources is also changing, and in some cases these values may cause conflict.

The main reasons people value natural resources are because they:

- support them to make a living, such as agriculture and tourism

- hold cultural significance

- provide environmental services, such as clean air and water

- provide recreational experiences

- provide natural beauty.

Population

The catchment has an estimated population of 215,000 people, which includes approximately 6,000 First Nations peoples, many of whom identify as Traditional Owners of the region (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016). Table 87 outlines the 4 population groupings, with town residents accounting for the majority of the population (Barr 2020).

Table 87: Goulburn Broken Catchment population groupings of where people live, from 2016 ABS Census data (Barr 2020)

| Classification | Description | Population count | Proportion of population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Town residents | City and town populations. | 134,087 | 74% |

| Rural residents | People living in rural areas not associated with a farm. | 30,176 | 17% |

| Part-time farmers | People associated with farms where no one has farming as their main occupation. | 10,532 | 6% |

| Full-time farmers | People living on farms where at least one person’s main occupation is farming. | 5,128 | 3% |

Emerging trends

Key trends for the catchment’s population since 2013 were identified by a socio-economic analysis of ABS census data (Barr 2020).

- The population is ageing faster than in major cities as young people move away for education and employment opportunities, inline with the rest of regional Victoria.

- Incomes remain low compared with the rest of Australia, with the population overrepresented in the lowest income group and underrepresented in the highest income group.

- The main trend in towns over the past 15 years has been a rise in employment in the health and education sectors and a decline in employment in manufacturing.

- The growth in town populations varies across the catchment and is mainly driven by town size, proximity to water or hills, facilities and employment in major centers, planning constraints, dependence on an industry with declining or growing employment and bushfire impacts.

- For those living outside towns, settlements are clustered a short distance of major towns and in the south in close proximity to Greater Melbourne. Low population density is seen in the mixed-farming corridor from Yarrawonga in the north to Avenel in the south and on the Strathbogie plateau.

- Many of the families outside towns draw an income from agriculture, but also get income from other employment such as health, education, construction, transport, accommodation, recreation and cafes.

Other important trends impacting the community were identified through stakeholder engagement. They include:

- Increasing recognition of the importance, benefits and legislated roles of Traditional Owners’ knowledge, decision-making and implementation. This means that Traditional Owner priorities and cultural values, whether they live on Country or elsewhere, influence the management of natural resources across the catchment.

- The growth in visitors for nature-based recreation being driven by increasing numbers of Australians living in major cities and regional centres.

- Water resources being used by those in the catchment and also shared beyond with users across the southern-connected Murray-Darling Basin.

- The growing number of people appreciating nature, working from home and/or moving to regional and rural areas as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Some groups and communities are more vulnerable to climate change impacts. For example, adverse health impacts are greatest among people on lower incomes, the elderly and those with poor health; while increased intensity and frequency of drought is likely to have serious social, emotional and economic impacts on agricultural communities.

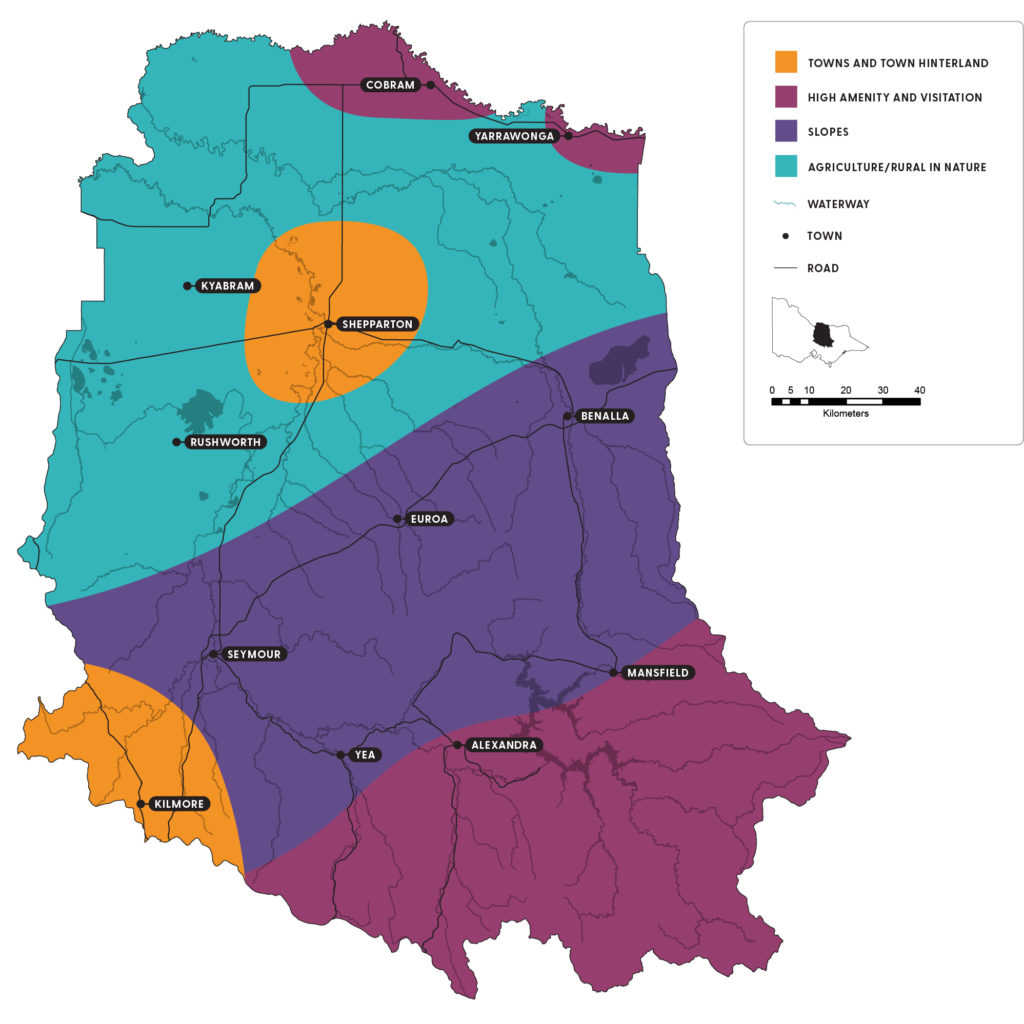

Table 88: Grouping of the socio-economic communities according to their major industry and use of natural resources

| Socio-economic cluster | Points of difference |

|---|---|

| Towns and town hinterland | People work in towns, have smaller properties and a higher income. |

| High amenity and visitation | Associated with water and the mountains and a high rate of absentee-owners. Includes the areas of Upper Goulburn, Strathmerton-Cobram, Yarrawonga, Nagambie and Southern Forests. |

| Slopes | Higher education, rapidly ageing population (possibly because of retirees moving in) and a low dependence on agriculture. Includes the areas of Benalla Hinterland, Hume Foothills and Upper Broken. |

| Agriculture/rural in nature | Predominantly agricultural, also has commuters/lifestylers on the poorer agricultural land. Includes a ring around Shepparton and to a less extent Murchison/Nagambite. |

Figure 38: Location of socio-economic communities according to their major industry and use of natural resources

Current condition

The capacity and resilience of the community is central to the catchment’s condition because community engagement in NRM is a major driver of biodiversity, land and water health.

The capacity and resilience of the community is strongly influenced by community health, wellbeing and education. Curiosity, capacity and an outward looking mindset rely on having basic needs met first. Improving community health, wellbeing and education builds overall community capacity and resilience, and has a positive impact on NRM.

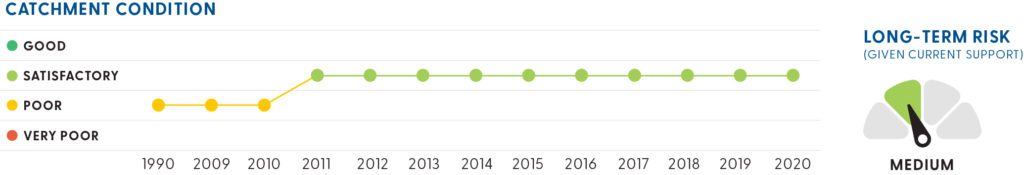

Qualitative condition ratings for the community’s capacity and resilience has been reported by the Goulburn Broken CMA since 1990. These ratings have been drawn from Goulburn Broken CMA annual reports, tipping points described by the community, socio-economic research and the community theme discussion paper developed as part of the strategy renewal. More information is available in Goulburn Broken CMA annual reports.

Figure 39 shows the trend in condition of community capacity and the long-term risk of decline with current support. The current condition is satisfactory, however the long-term risk of decline is medium.

Figure 39: Trends in the condition of the Goulburn Broken Catchment’s community capacity and resilience since 1990 and the long-term risk of decline in condition given current support levels

Trends in capacity and resilience

The community’s resilience has strengthened following the experience of significant threats to the environment and economy in the late 1980s and 1990s. Community leaders recognised the complexity of the threats, uncertainties about responding and the need for a whole-of-catchment response. Governments devolved significant responsibilities and decision-making to local communities, enabling them to determine their future in the face of emerging environmental problems.

The Landcare movement grew during this period with recognition of the need for knowledge sharing and coordinated action beyond individual property boundaries. Integrated catchment management, with strong partnerships between communities and government, was at the core of the approach. Communities demonstrated their ability to self-organise and adapt to change and the movement led to the establishment of many diverse groups.

However, the increasing urgency to improve the catchment’s natural resources, combined with increasing and competing priorities for public resources, means communities need to explore new investment opportunities. Additionally, the increasing diversity of landholders, use and connection to nature are driving a rethink about how we maintain local links and support while providing opportunities for transient volunteering.

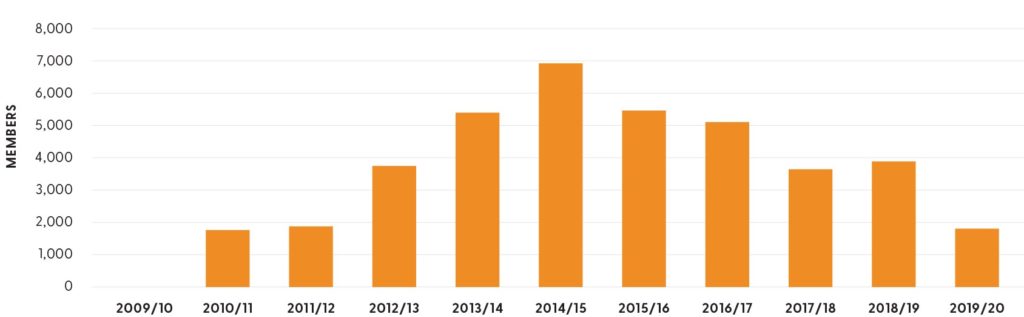

A voluntary survey of the catchment’s volunteer-based environment and sustainable farming groups is undertaken each year to monitor group health and activity. Table 89 provides a snapshot of group health across the catchment, although it should be noted not all groups complete the survey each year. Groups also report volunteer membership numbers each year (Figure 40), although completion of the survey in 2019-20 was lower than normal as funding wasn’t linked to completion of the survey. Further details on the survey results are available in community NRM report cards.

Table 89: Group health results of the catchment’s volunteer-based environment and sustainable farming groups. Source: Victorian Landcare Program Group Health Survey for Goulburn Broken

| Group health score | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Just hanging on | 3 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| Struggling along | 5 | 16 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 9 | 7 |

| Moving forward | 22 | 23 | 28 | 19 | 23 | 26 | 13 | 9 |

| Rolling along | 11 | 17 | 17 | 11 | 16 | 14 | 8 | 5 |

| Trail blazers | 3 | 4 | 7 | 13 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 2 |

| Total | 44 | 67 | 68 | 59 | 65 | 68 | 39 | 24 |

A positive trend emerging in the community is the increasing recognition and inclusion of Traditional Owners in NRM. Traditional Owner knowledge is reflected in the management of the catchment’s land, water and biodiversity.

The roles of the Taungurung Land and Waters Council and the Yorta Yorta Nation Aboriginal Corporation in catchment management are expanding as greater acknowledgement of cultural aspirations and traditional ecological knowledge provide new opportunities. Legislative changes have also formalised co-management of specific areas, legal obligations for managers of Crown land and the greater involvement of Traditional Owners in catchment planning.

These changes have resulted in more complex and sophisticated processes for decision-making and implementation and have highlighted the need for more resources in this area.

Community capacity to influence and lead, be involved and act on-ground, are critical attributes for long-term community resilience. While the catchment’s current condition for the community is satisfactory, significant adaptation and transformation is required to:

- build community resilience to change

- activate community interest and stewardship in environmental issues

- engage the increasingly diverse community and range of visitors

- strengthen community leadership and influence in decision-making

- increase community capacity to be involved and act on-ground.

Drivers of change

Drivers of change influence how the catchment operates and can shape future pathways. What we do now will influence the capacity and resilience of community in the future. In addition, unanticipated or acute shocks, such as pandemics, industry adjustment or drought, can impact the catchment dynamics and community.

Tables 90-96 outline the 7 major drivers of change impacting community involvement in NRM. They were identified through community engagement and socio-economic analysis as part of the strategy renewal:

- transition to a service economy

- increasing and competing priorities for public resources and an urgency to improve natural resources

- climate change

- changing relationship with nature

- growing diversity of landholders

- increasing awareness of First Nations culture

- changes to volunteering.

Driver 1: Transition to a service economy

Table 90: Catchment trends and impacts for community from a transition to a services economy

| Catchment trends | Impacts for community |

|---|---|

| • Aggregation of the population in towns and hinterlands surrounding major towns. • More urban development in areas with access to Melbourne and larger towns, increasing number of lifestyle properties close to towns and in high amenity areas, and more weekender properties in high amenity areas. • Increasing land prices where urbanisation and lifestyle properties are expanding. • Declining percentage of people that earn an income off the land. | • Sensitive and valuable habitat is threatened by urban development. • Increasing visits to natural and high amenity areas for nature-based recreation, weekends away and sport. • Increasing disconnect between where people live, how they make a living and the natural resources they use and enjoy. • Visitors are unaware of their impact and make no contribution to ameliorating their impacts. • More opportunity to involve urban volunteers in the regional areas they visit for recreation, tourism or holidays. |

Driver 2: Increasing and competing priorities for public resources and an urgency to improve natural resources

Table 91: Catchment trends and impacts for community from increasing and competing priorities for public resourcs and an urgency to improve natural resources

| Catchment trends | Impacts for community |

|---|---|

| • Increasing community and government interest and expectations for engagement, collaboration and partnerships with Traditional Owners. This increases the need for more resources in this area. • There is an increased challenge for community groups to balance the accountability requirements of community grants (for example, competitive grant and tender processes and reporting) and the volunteer resources. | • Limited resources for groups and organisations to engage or work with Traditional Owners, particularly those that don’t live on Country. • Limited resources to integrate Traditional Owner knowledge and protect cultural sites. • Reduced participation in NRM community groups, contribution of in-kind and volunteer resources. • Increasing demand on landholders involved in NRM for other volunteer roles, resulting in burn-out. • Growing list of landholders waiting for revegetation funding, providing opportunities when funding is available. |

Driver 3: Climate change

Table 92: Catchment trends and impacts for community from climate change

| Catchment trends | Impacts for community |

|---|---|

| • A hotter and drier climate. • Reduced reliability of rainfall in spring and autumn. • Increased frequency and intensity of storms, heatwaves, bushfires and droughts. | • Threatens the viability of existing agriculture and snow-based industries and therefore job opportunities. • Threatens the amenity and recreation values of native vegetation, rivers, streams, lakes and alpine areas. • Threatens community health. • Exhausts the community’s financial, physical and emotional resources to recover and grow. • Threatens visitor and resident confidence in the region as a safe place to visit and live. • Increasing acceptance across the community that climate is changing. • Growing financial and infrastructure sectors in support of green investments. • Increasing urban reforestation to lower urban temperatures. • Increasing interest and partnerships between environment and health sectors. • Opportunity to link city visitors with options to offset their climate change impacts. |

Driver 4: Changing relationship with nature

Table 93: Catchment trends and impacts for community from a changing relationship with nature

| Catchment trends | Impacts for community |

|---|---|

| • Different approaches are required to engage different worldviews of nature held by the community.* • Younger generations are learning about the need to protect the environment for future generations, but it will be at least 10 years before they are decision makers. | • Increased need to connect with the community through their use of natural resources, such as amenity and recreation. • Need to better engage with the range of worldviews, which may mean tailoring communication messages to suit each worldview. For example, we cannot assume that everyone values water the same way, or is mindful of their environmental impacts. |

Driver 5: Growing diversity of landholders

Table 94: Catchment trends and impacts for community from the growing diversity of landholders

| Catchment trends | Impacts for community |

|---|---|

| • The different types of landholders (public, farmers, lifestyle, absentee or weekenders) have different motivations, capability and time available to act as stewards for the land, native vegetation and water assets. • Some landholders live outside the catchment and only visit on weekends or for holidays, for example, almost 50% of properties in the Mansfield Shire are owned by people that doesn’t live there. • Land is being adapted and transformed in response to changing conditions, such as markets and climate, which is increasing the diversity of land use and management practices. | • Increasingly difficult to address the range of natural resource issues, and ensure the sustainability of current practices, where a collective effort is required. • Greater acknowledgement and recognition of the increasing diversity of rural and regional communities. • A need to develop different ways to connect with landholders that live outside the catchment. |

Driver 6: Increasing awareness of First Nations culture

Table 95: Catchment trends and impacts for community from increasing awareness of First Nations culture

| Catchment trends | Impacts for community |

|---|---|

| • Greater inclusion of Traditional Owners in NRM. • Strategic policies promote greater involvement of Traditional Owners in catchment planning, such as the Water for Victoria plan, Goulburn Broken CMA memorandum of understanding with the Yorta Yorta Nations Aboriginal Corporation, National Water Initiative, and the Taungurung Recognition and Settlement Agreement. • Legislative changes formalise co-management of specific areas and legal obligations for managers of Crown land. • Greater acknowledgement of cultural aspirations documented in Country Plans, which provide guidance and work plans for Traditional Owner groups. | • Growing recognition of Traditional Owner aspirations and inherent rights to natural resources. • The Taungurung Land and Waters Corporation and the Recognition and Settlement Agreement provide for active participation and access to Country. • Greater acknowledgement, integration and incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge. • Greater need for resourcing traditional ecological knowledge properly. • More complex processes for decision-making and implementation of NRM on Crown land with co-management legislation. • Increasing tension where public land has competing use, such as conservation, recreation, cultural and forestry. • Opportunity to raise the awareness of Traditional Owner roles and the ethics of Caring for Country. • Opportunity to promote visitation through cultural interpretation and experiences with Traditional Owners. |

Driver 7: Changes to volunteering

Table 96: Catchment trends and impacts for community from changes to volunteering

| Catchment trends | Impacts for community |

|---|---|

| • Decline in traditional natural resource groups and place-based participation. • More issue-based volunteering. • Increased interest in participating in one-off events and online. | • Many community and advisory groups are ageing due to work-life demands of younger generations and changing population demographics. • Need to develop new approaches to involve people in one-off and issue-focussed volunteer opportunities. |

Tipping points

Understanding and identifying tipping points of significant change is important to increase the resilience of the catchment and its social, economic and environmental services. Significant change occurs when the characteristics of a system change so much that the system is no longer the same. A tipping point, or threshold, is a critical level of one or more variables. When crossed, it triggers abrupt change in the system that may not be reversible (Wayfinder 2021).

Some tipping points are well understood and can be used to track progress and guide management, while our understanding of others is still developing. It is a key outcome of the strategy to build our understanding of tipping points and how to apply them through partnerships and research projects with a range of organisations. This strategy outlines which tipping points are important to understand and monitor. In some circumstances tipping points have been exceeded and we need to establish targets to stabilise system function. Further information about tipping points is available here.

Table 97 outlines the data-driven tipping points for community capacity in NRM that will be further investigated during the life of the strategy.

Table 97: Data-driven tipping points for community capacity that will be investigated during the implementation of the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy

| Critical attribute | Tipping point of interest |

|---|---|

| Community capacity to influence and lead. | • Identify the level of investment required in community-led NRM to empower local communities. |

| Community capacity to be involved and act on-ground. | • Identify the percentage of community that needs to value environmental stewardship to improve catchment condition. |

For further information about the tipping points click here.

Outcomes and strategic directions

Vision

A motivated and connected community leads positive change for people, land, water and biodiversity.

Outcomes and strategic directions

Table 98 outlines long (20-year) and medium-term (6-year) outcomes for the capacity and resilience of the catchment’s community. It also presents strategic directions for each long-term outcome. Please note, the outcomes are complementary and consideration of all outcomes is required during implementation to achieve the vision.

Table 98: Desired long (20-year) and medium-term (6-year) outcomes for the community and the associated strategic directions

| Long-term outcomes (by 2040) | Medium-term outcomes (by 2027) | Strategic directions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Activate community interest and stewardship in NRM. | • Increase the diversity of community and visitors engaged in the health of the catchment. • Increase the diversity of land managers engaged in projects to improve the health of the catchment. | • Mechanisms are in place to create and maintain environmental stewards. |

| 2. Strengthen community leadership and influence on decision-making. | • Identify and provide mentoring and training to 25 new and emerging local NRM leaders. • Identify opportunities to support and promote 50 local NRM leaders to influence decision-making at a range of levels. • NRM related boards and advisory groups are representative of the diverse community. | • Build natural resource leadership skills and influence across the diverse community. • Respond to Traditional Owner priorities to build natural resource leadership, management decision making and implementation capacities. |

| 3. Increase community capacity to be involved and act on-ground. | • Improve the capacity of existing and new community groups and organisations to be involved in NRM and act on-ground. • Form 5 partnerships with new sectors that attract resources and investment for community-led action. • Provide new opportunities to build the capacity of a range of community members be involved and act on-ground. • Increase the opportunities for volunteer participation by 25% with the adoption of new models of volunteering. | • Investigate and develop new opportunities for the diverse community to be involved in responsible use and protection of the natural environment. • Build the capacity of existing and new community groups to be involved in NRM and act on-ground. • Strengthen relationships with non-traditional partners to diversify opportunities for NRM. |

Priority actions

Priority actions provide ideas and options for the future, rather than fixed work plans. Actions must evolve as the catchment changes and new information becomes available.

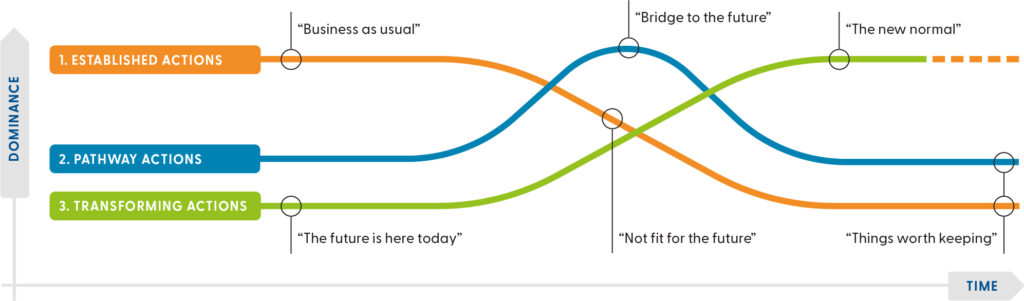

Tables 99-101 present priority actions for each long-term outcome as:

- Established actions, which are those currently occurring that we would like to continue. They include business as usual, recognised and existing practices. These actions are widespread and well-understood.

- Pathway actions, which are innovations that help us shift from the current situation to an ideal future. For example, experiments, bridging or transition actions that take place during the transition from established to transforming actions.

- Transforming actions, which are the way we want things to work in the future. For example, the new normal, visionary ideas and new ways of doing things to create change. There may be pockets of these already happening.

A combination of all 3 types of actions is required to achieve the vision for the future (Figure 41).

Dividing actions this way is based on the Three Horizons framework and helps communities:

- think and plan for the longer-term by identifying emerging trends that might shape the future

- understand why current practices might not lead to a desired future

- recognise visionary actions that might be needed to get closer to a desired future.

Long-term outcome 1: Activate community interest and stewardship in NRM by 2040

Table 99: Priority actions required to help achieve long-term outcome 1

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established | • Understand and build on the diversity of connections and benefits the community has with the environment. • Engage with all levels of education to share the messages of environmental protection, volunteering and sustainable agriculture. • Engage the community and visitors in citizen science programs to monitor catchment health. • Improve awareness of the community and visitors of information, contacts and services to support NRM, for example, new landholder information packs and farm planning courses. • Create opportunities for urban communities to engage with NRM. |

| Pathway | • Increase links between non-traditional community groups and NRM activities. • Support the development of virtual hubs for community members and visitors to access information, resources and contacts in NRM. • Strengthen the connection of weekenders and visitors to the catchment and provide opportunities to make a positive difference to the environment. • Support nature-based tourism to increase community connection with nature and provide economic benefits to the catchment. • Quantify the public benefits provided by NRM, such as health and recreation. • Identify strategic alignment and collaboration opportunities between NRM and education, health and community. |

| Transforming | • Build environmental stewardship* so that it is embraced by the entire community, including visitors, and leads to collaboration between diverse groups and sectors that use, manage, fund or care for natural resources. • The urban community and visitors make stewardship payments to public and private land managers to offset their environmental impact and contribute funds for use in NRM projects. |

Long-term outcome 2: Strengthen community leadership and influence on decision-making by 2040

Table 100: Priority actions required to help achieve long-term outcome 2

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established | • Identify the NRM related boards and advisory groups in the catchment and provide pathways to diversify their membership. • Sponsor participation in community leadership programs and training. • Create links between government and community to allow issues to be heard where and when decisions are made. • Advocate for government funding to address community needs. • Build capacity of local leaders in resilience thinking and implementation. • Public land managers and government organisations regularly consult and collaborate with Traditional Owners on NRM planning and implementation. |

| Pathway | • All stakeholder groups have a voice in NRM decision making at local and regional levels, for example, different livelihood, lifestyle, ethnic, cultural and age groups. • Greater interest and inclusion of Traditional Owner ecological knowledge and First Nations culture in the community. • Engage local government youth councils in NRM issues and decision-making. |

| Transforming | • Create decision-making processes at the local and regional levels that reflect the diversity of the community. • Private land managers and businesses regularly consult and collaborate with Traditional Owners on NRM planning and implementation. • Traditional Owners lead NRM decision making and implementation on public land. • A catchment-wide NRM youth council influences NRM programs and decision-making. |

Long-term outcome 3: Increase community capacity to be involved and act on-ground by 2040

Table 101: Priority actions required to help achieve long-term outcome 2

| Action type | Priority actions |

|---|---|

| Established | • Understand and promote the value of volunteering, such as the social, personal, health and environmental benefits. • Support existing volunteer groups to maintain momentum. • Support paid community coordinators/facilitators to assist and deliver volunteer engagement and community education activities. • Build awareness and understanding among the community of catchment NRM issues and priority actions identified to address them. • Support paid community coordinators/facilitators to assist and deliver volunteer engagement and community education activities. • Build resilience by growing the connection between government and community networks. • Increase opportunities for integrating scientific, lived and traditional knowledge into planning, action and monitoring. • Ensure that funding opportunities are maximised with partnerships and collaboration, rather than competition. • Support existing forums such as the Goulburn Broken Local Government Biodiversity Reference Group, Goulburn Broken Partnership and the Goulburn Broken Community Network Chairs. • Create opportunities for all individuals, volunteers, groups, agencies and businesses involved in NRM to share knowledge, exchange ideas, discuss emerging issues and collaborate. • Strengthen Traditional Owner capabilities with participation in implementation. • The strategy and associated local area plans are co-developed with community and guide community-led NRM at local and regional levels. |

| Pathway | • Create volunteer opportunities for visitors. • Support NRM groups and networks to offer engagement events that embrace community diversity. • Investigate and develop programs that successfully engage visitors and corporate volunteers in NRM. • Increase the capacity of groups to cope with disasters, such as bushfires, floods and pandemics. • Build an understanding of resilience and practical options that create capacity to anticipate, absorb, respond, recover and renew when change occurs. • Ensure community-related, resilience building opportunities are fair and inclusive, with focus on vulnerable communities. • Strengthen relationships with private investment sectors to diversify revenue for NRM. • Identify non-traditional partners each year so new opportunities are recognised and developed. • Demonstrate the community benefits of investment in NRM, such as health, carbon offsets and so on. • Investigate new models of engagement and investment in NRM. |

| Transforming | • A broad range of people volunteer their time and/or resources to a wide variety of NRM projects. • Investment from a range of sectors, such as health, transport and tourism, deliver NRM projects for dual benefits. • Our communities and regions have the power, capacity and resources to adapt to climate change, leaving no one behind. |

Tracking progress

Monitoring outcomes

Progress towards the community theme outcomes will follow the strategy’s evaluation and adaptation framework outlined here.

Reporting condition

Catchment condition for the community will be reported annually through state-wide indicators, as part of the Goulburn Broken CMA Annual Report:

- community volunteering, including Landcare and community NRM group health score

- number of formal partnership agreements for planning and management between Traditional Owners and NRM agencies

- number of partnerships involved in integrated catchment management.

Monitoring tipping points

Tipping points for the community critical attributes will be monitored where possible:

- community capacity to influence and lead.

- community capacity to be involved and act on-ground

References and further information

Aither (2019) Goulburn Regional Profile: An analysis of regional strengths and challenges [PDF 3.08MB], report to Infrastructure Victoria, Aither Pty Ltd.

Barr N (2018) Socio-economic indicators of change – Goulburn Broken and North East CMA Regions [PDF 21.31MB], Natural Decisions Pty Ltd.

Tyler Miller G and Spoolman S (2021) ‘Environmental Worldviews, Ethics, and Sustainability’ [PDF 3.62MB], in Living in the environment, Cengage Learning, USA.

Goulburn Broken CMA (Catchment Management Authority) (n.d.) Community NRM Report Card, Goulburn Broken CMA.

Goulburn Broken CMA (Catchment Management Authority) (2020) Goulburn Broken Regional Insights Paper 2020 [PDF 5.64MB] Goulburn Broken CMA.

Greater Shepparton City Council (2017) 2018-2028 Public Health Our Strategic Focus, Greater Shepparton City Council.

Murray River Region Tourism Ltd (2020) Murray Regional Tourism 2019-2020 Annual Report [PDF 3.13MB], Murray River Region Tourism Ltd.

Show your support

Pledge your support for the Goulburn Broken Regional Catchment Strategy and its implementation.